Embark on an exploration of Protoceratops, a captivating dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous Period. This ancient creature, whose name intriguingly means “First Horned Face,” offers a glimpse into a long-gone era of our planet’s history. Discovered in the expansive Gobi Desert, Protoceratops has been a subject of fascination and study since its initial discovery in the early 20th century.

In this in depth article, we’ll unravel the mysteries surrounding Protoceratops. From its unique physical characteristics and dietary habits to its place in the dinosaur family tree and the environment it roamed, this journey will enhance your understanding of one of the most intriguing dinosaurs that once walked the Earth.

Protoceratops Key facts

| Keyword | Fact |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | pro-toe-ser-ah-tops |

| Meaning of name | First Horned Face |

| Group | Ceratopsia |

| Type Species | Protoceratops andrewsi |

| Diet | Herbivore |

| When it Lived | 145.0 to 70.6 MYA |

| Period | Late Cretaceous |

| Epoch | Campanian |

| Length | 6.6 to 8.2 feet |

| Height | Approximately 2.5 feet |

| Weight | 140 to 300 pounds |

| Mobility | Moved on two legs |

| Described by | 1923, Granger and Gregory |

| Holotype | AMNH 6251 |

| Location of first find | Gobi desert, in Gansu, Inner Mongolia |

| Also found in | China |

Protoceratops Origins, Taxonomy and Timeline

The name Protoceratops alludes to the dawn of horned dinosaurs, and has its roots embedded in Greek etymology. The term aptly describes a creature that at the time of its initial discovery was believed to represent the earliest member of the lineage of horned dinosaurs to which the famous Triceratops also belongs.

In the grand tapestry of dinosaur taxonomy, Protoceratops belongs to the Ceratopsia group of ornithischian dinosaurs. This collection of herbivorous dinosaurs is known for their beaked faces and frilled skulls that were often adorned with a crazy variety of horns and spikes. More specifically, it falls under the Protoceratopsid family, a lineage that showcases a variety of unique physical traits.

The timeline of Protoceratops spans a significant portion of the Late Cretaceous Period. This era, ranging from 100.5–66 million years ago, witnessed the evolution and diversification of numerous dinosaur species. Protoceratops thrived during this dynamic epoch, adapting to and flourishing within its environment.

Listen to Pronunciation

Check out this video for the correct pronunciation of Protoceratops.

Pioneering Expeditions of Protoceratops Discovery

The journey to uncover the secrets of Protoceratops began in the early 20th century, sparked by Henry Fairfield Osborn’s hypothesis about Central Asia being a cradle of diverse species. This led to a series of Central Asiatic Expeditions, notably the First (1916-1917), Second (1919), and Third (1921-1930), organized by the American Museum of Natural History. Roy Chapman Andrews, a renowned explorer and zoologist, played a pivotal role in these expeditions. The third expedition, particularly in 1922, made significant strides in the Flaming Cliffs of the Gobi Desert, leading to the discovery of the holotype specimen of Protoceratops. This juvenile skull, found by photographer James B. Shackelford, was a gateway to numerous other dinosaur fossils, enriching our understanding of Asia’s prehistoric life.

In 1923, the team revisited the Flaming Cliffs, unearthing an even greater array of Protoceratops specimens and the first fossilized dinosaur eggs. These discoveries, initially attributed to Protoceratops, played a crucial role in shaping our perceptions of dinosaur reproduction and behavior. The expeditions, under Andrews’ leadership, not only brought to light Protoceratops but also other significant species like Oviraptor, Saurornithoides, and Velociraptor.

The Impact of the Expeditions

The expeditions of the 1920s, particularly those between 1922 and 1925, represented a golden era for the field of paleontology, driving an increased appreciation for the regional diversity of the prehistoric world. These expeditions yielded a rich collection of over 100 specimens of Protoceratops, including skulls and skeletons at various growth stages. The abundance and quality of these finds allowed for a deeper understanding of Protoceratops’ anatomy and its place in the dinosaur lineage, ultimately establishing it as the prevalent species of the region during this point of the Late Cretaceous.

The Enigma of Protoceratops Eggs

The 1923 expedition led to a groundbreaking discovery – the first known fossilized dinosaur eggs. Found near the holotype of Oviraptor, these eggs were initially thought to belong to Protoceratops, casting Oviraptor as an egg-thief. This interpretation, influenced by the proximity of the eggs to abundant Protoceratops fossils, demonstrates how easy it can be to draw a significant relationship between two seemingly connected pieces of evidence in the fossil record – especially when directly observing behavior is so difficult if not downright impossible!

Reevaluation and Authentic Protoceratops Nests

Subsequent research and discoveries, however, painted a different picture. In the 1990s, a theropod embryo found within an eggshell typical of those initially attributed to Protoceratops suggested that these eggs were actually laid by oviraptorids. This revelation not only cleared Oviraptor’s name but also prompted a reevaluation of Protoceratops’ reproductive habits. Authentic nests of Protoceratops, discovered later, provided a clearer understanding of their nesting and early life stages.

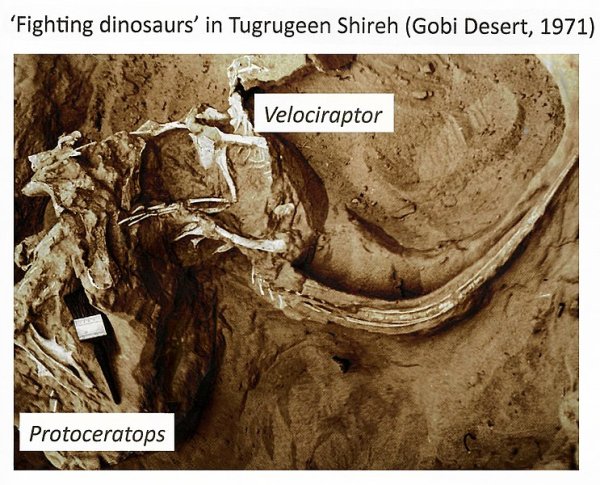

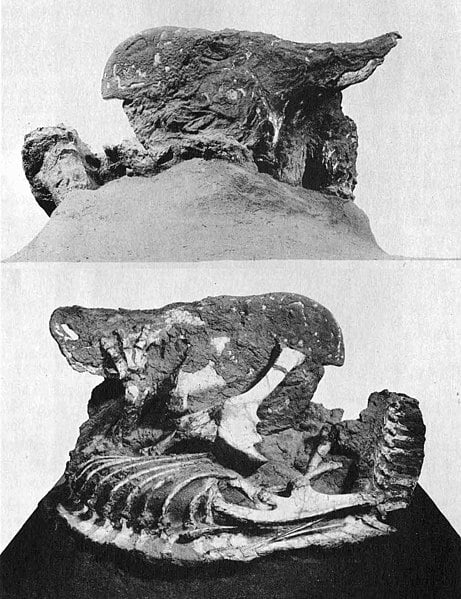

The Legendary Fighting Dinosaurs

One of the most sensational finds in the study of Protoceratops was the discovery of the ‘Fighting Dinosaurs’ specimen in 1971. Found during a Polish-Mongolian expedition in the Gobi Desert, this remarkable fossil captured a Protoceratops and a Velociraptor locked in combat. This discovery offered a rare, frozen-in-time glimpse of predator-prey interactions among non-avian dinosaurs.

Interpretations and Significance

The ‘Fighting Dinosaurs’ specimen has been the subject of extensive study and debate. The prevailing theory suggests that these two dinosaurs were buried alive, possibly by a sudden sandstorm or a collapsing dune, capturing their final struggle for eternity. This extraordinary find not only provides direct evidence of behavioral interactions but also serves as a testament to the dynamic and perilous world these creatures inhabited.

Mounted P. andrewsi skeleton,

Mounted P. andrewsi skeleton, Holotype skull of P. andrewsi, collected during the Third Central Asiatic Expedition

Holotype skull of P. andrewsi, collected during the Third Central Asiatic Expedition Protoceratops hellenikorhinus. Prehistoric Gallery, Inner Mongolia Museum, Hohhot, China.

Protoceratops hellenikorhinus. Prehistoric Gallery, Inner Mongolia Museum, Hohhot, China. Protoceratops andrewsi. Two views of a skeleton in an unusual curled up position showing a thin, indurated layer of matrix over the head region which has a very skin-like appearance.

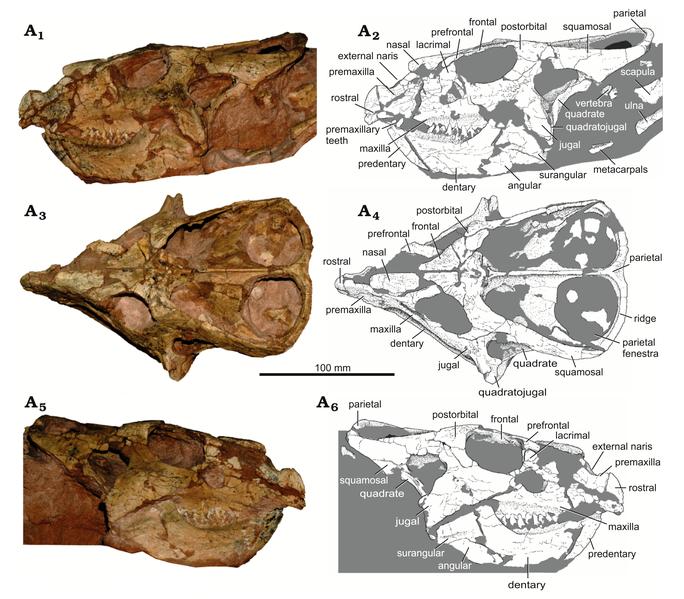

Protoceratops andrewsi. Two views of a skeleton in an unusual curled up position showing a thin, indurated layer of matrix over the head region which has a very skin-like appearance. Skull of P. andrewsi (MPC-D 100/551) in left lateral (A1-A2), dorsal (A3-A4), and right lateral (A5-A6) views

Skull of P. andrewsi (MPC-D 100/551) in left lateral (A1-A2), dorsal (A3-A4), and right lateral (A5-A6) views Skull of P. andrewsi (MPC-D 100/505) in right lateral (A1) and left lateral (A2) views

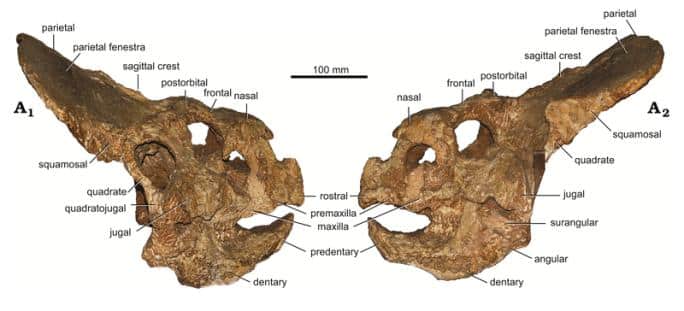

Skull of P. andrewsi (MPC-D 100/505) in right lateral (A1) and left lateral (A2) views P. andrewsi skull

P. andrewsi skull Protoceratops andrewsi growth series.

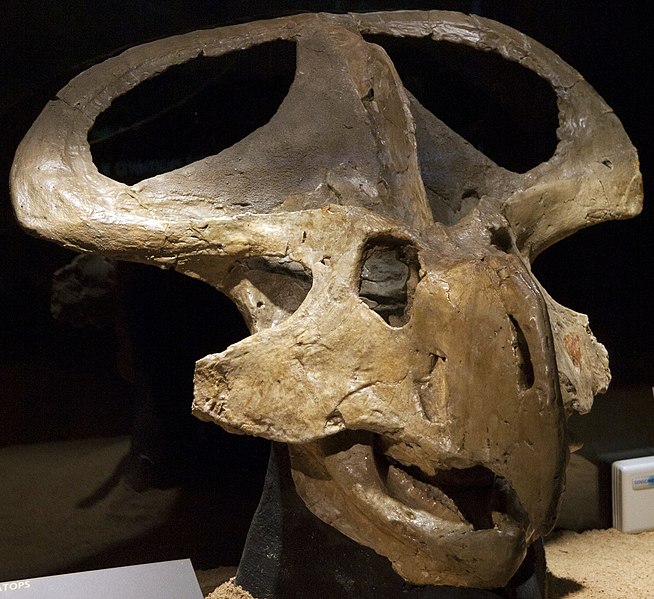

Protoceratops andrewsi growth series. P. hellenikorhinus skull

P. hellenikorhinus skull Protoceratops andrewsi, first horned-face

Protoceratops andrewsi, first horned-face Fossil cast of P. andrewsi showing left hindlimb, equipped with large, flat, shovel-like unguals

Fossil cast of P. andrewsi showing left hindlimb, equipped with large, flat, shovel-like unguals Elevated neural spines of the caudal (tail) vertebrae of an assigned Protoceratops specimen

Elevated neural spines of the caudal (tail) vertebrae of an assigned Protoceratops specimen P. andrewsi specimen MPC-D 100/534

P. andrewsi specimen MPC-D 100/534 Skeletal mount of Protoceratops with juveniles

Skeletal mount of Protoceratops with juveniles Skull of P. andrewsi AMNH 6466, preserving sclerotic ring

Skull of P. andrewsi AMNH 6466, preserving sclerotic ring Cast of the Fox site Protoceratops, a largely bored P. andrewsi (note reconstructed rostrum)

Cast of the Fox site Protoceratops, a largely bored P. andrewsi (note reconstructed rostrum) Original photograph of the upper part of the Protoceratops skeleton (view 1) taken during Polish-Mongolian Paleontological Expedition to Gobi Desert known in scientific literature as ‘Standing Protoceratops’

Original photograph of the upper part of the Protoceratops skeleton (view 1) taken during Polish-Mongolian Paleontological Expedition to Gobi Desert known in scientific literature as ‘Standing Protoceratops’ Juvenile from MPC-D 100/526; black arrow points to larvae borings

Juvenile from MPC-D 100/526; black arrow points to larvae borings P. andrewsi specimen MPC-D 100/534; note borings on the rostrum

P. andrewsi specimen MPC-D 100/534; note borings on the rostrum

The Ultimate Dino Quiz

Do you want to test your knowledge on dinosaurs? Then try this Ultimate Dino Quiz! Don’t worry if you get some of the answers wrong, and look at it as an opportunity to refresh and improve your knowledge!

Don’t forget to try our other games as well!

Protoceratops Size and Description

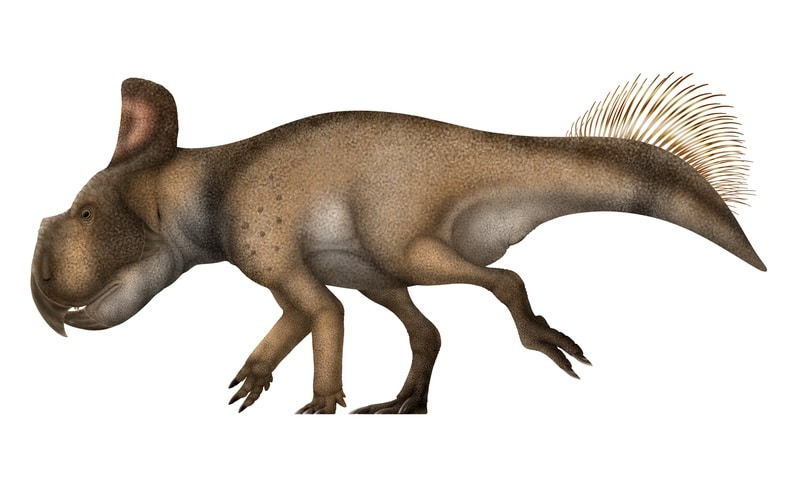

Protoceratops was somewhat unique for ceratopsian dinosaurs. Unlike its larger relatives, which often sported large horns above the brow, along with a diverse array of frill ornamentation, the Protoceratops skull was conspicuously devoid of any such embellishments. The characteristic ceratopsian frill was still present however, as was the parrot-like beak. These features, along with its strongly pointed cheek-bones, resulted in a highly robust skull that would have appeared rather large in comparison to its body. A subtle swelling above the nasal bones suggests that some individuals (possibly males) possessed a short horn-like structure above the snout.

Size and Weight of Type Species

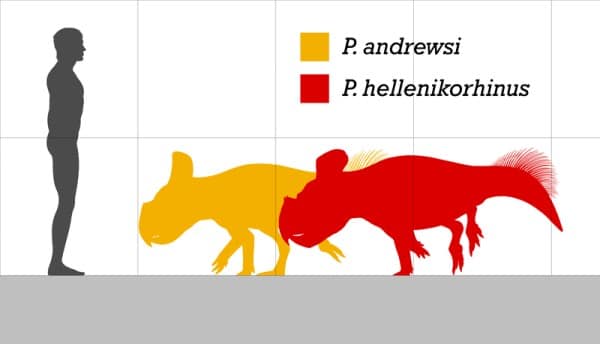

Protoceratops was relatively diminutive for a ceratopsian, with both P. andrewsi and P. hellenikorhinus measuring up to 6.6 to 8.2 feet in length and weighing around 137.0 to 229.0 pounds. Despite their similar body sizes, P. hellenikorhinus boasted a relatively longer skull. The two species exhibited distinct characteristics: P. andrewsi featured a low, long snout with a single, pointed nasal horn and a slightly curved bottom edge of the dentary, while P. hellenikorhinus had a tall, broad snout without premaxillary teeth, a nasal horn divided into two pointed ridges, and a straight bottom edge of the dentary.

The skull of Protoceratops was notably large in proportion to its body, robustly built, and varied in size between species. The type species, P. andrewsi, had an average skull length of nearly 20 inches, whereas P. hellenikorhinus had a skull length of about 28 inches. The rear of the skull formed a pronounced neck frill, mostly composed of the parietal and squamosal bones, with its size and shape varying among individuals. Some had short, compact frills, while others had frills nearly half the length of the skull, showcasing the diversity within the species.

Interesting Points about Protoceratops

- The name Protoceratops’ originally stems from the belief that this dinosaur was amongst the first dinosaurs to exhibit a frill; however; we now know it existed at around the same time as some truly monstrous ceratopsians such as Centrosaurus and Chasmosaurus.

- Despite its name suggesting a horned face, Protoceratops did not have prominent horns like its larger cousins.

- The discovery of Protoceratops eggs in the Gobi Desert provided crucial evidence for understanding dinosaur reproduction.

- Protoceratops fossils have played a key role in the study of dinosaur skin impressions, offering insights into their texture and appearance.

- The mid-tail of Protoceratops expanded into a heightened, sail-like structure. The function of this feature remains debated to this day.

Protoceratops: Unraveling Its Natural World

Protoceratops, from the Late Cretaceous Period, exhibited intriguing feeding habits. Paleontologists, through detailed study of its skull and teeth, have deduced much about its diet and eating methods. The large neck frill, for instance, likely served as an anchor for masticatory muscles, aiding in feeding. The structure of its teeth, particularly the maxillary teeth arranged into a dental battery, suggests that Protoceratops was adept at chopping and grinding leaves, a primary component of its diet. The coarsely-textured enamel and micro-serrations on its teeth were likely instrumental in crumbling vegetation.

Contrary to the traditional view of Protoceratops as a strict herbivore, some experts propose that it might have been an opportunistic omnivore. Its parrot-like beak and shearing teeth, coupled with powerful jaw muscles, suggest a diet that could occasionally include animal matter, akin to the feeding habits of pigs or boars. Although this idea has yet to achieve consensus, this omnivorous tendency – if accurate – indicates a complex ecological role for Protoceratops.

Locomotion and Movement

Understanding how Protoceratops moved is key to picturing its life in the Cretaceous landscape. It was likely an obligate quadruped, given the proportions of its limbs, moving primarily with a trot-like gait. In certain situations, such as escaping danger or foraging, it may have adopted a rapid, facultative bipedalism. The flat and wide pedal unguals of Protoceratops were well-suited for traversing loose, sandy terrain, a common feature of its habitat.

The forelimbs of Protoceratops, while easily capable of reaching the ground, were not primarily used for locomotion, with the main propulsive force generated by the hindlimbs. This dinosaur’s movement was characterized by a significant lateral mobility in its spine, allowing for agile maneuvering, while its neck region was less flexible. The discovery of a fossilized footprint suggests that Protoceratops was digitigrade, walking on its toes.

Digging Behavior and Tail Function

Protoceratops may have engaged in digging behaviors, using its hindlimbs equipped with large, flat, shovel-like unguals. This activity could have been for creating burrows or seeking shelter under vegetation, a strategy to escape the harsh daytime temperatures. The robust nature of its limbs and the evidence of some specimens found in burrow-like positions support this theory.

The tail of Protoceratops also presents an interesting aspect of its anatomy. While some early theories suggested aquatic adaptations, more recent interpretations lean towards a desert-adapted lifestyle. The elevated neural spines on its tail might have been used for fat storage, similar to some modern desert lizards, or as a means to shed excess heat. This adaptation would have been crucial for surviving in the arid environments of the Djadokhta Formation.

Social Behavior and Group Dynamics

Evidence suggests that Protoceratops was a social dinosaur, forming herds throughout its life. Fossil assemblages indicate that these herds varied in composition, including adults, sub-adults, and juveniles. The tendency to form groups likely provided increased protection against predators and environmental challenges. The discovery of multiple individuals in close proximity, with similar orientations, reinforces the idea of Protoceratops as a gregarious creature, possibly forming herds for defense and social interaction.

In summary, Protoceratops navigated a complex world, adapting its diet, movement, and social behaviors to the challenges of its environment. These adaptations not only ensured its survival but also shaped the ecosystem in which it lived.

Frequently Asked Questions

Protoceratops means ‘First Horned Face,’ a reference to its distinctive facial features.

It was first discovered in 1920 in the Gobi Desert.

Protoceratops was a herbivore, primarily feeding on plants.

It primarily moved on four legs; although younger individuals may have been able to adopt a bipedal gait if certain instances called for a brief burst of speed!

Most Protoceratops fossils have been found in China and Mongolia.

Its large skull with a frill and a beaked mouth are distinctive features.

Sources

The information in this article is based on various sources, drawing on scientific research, fossil evidence, and expert analysis. The aim is to provide a comprehensive and accurate overview of Protoceratops. However, please be aware that our understanding of dinosaurs and their world is constantly evolving as new discoveries are made.

Article last fact-checked: Joey Arboleda, 12-14-2023