The Parksosaurus might not be as famous as some of its contemporaries, but it certainly has a tale worth telling. Discovered in the rugged terrains of Alberta, Canada, it offers us a unique glimpse into a world long gone. Join us as we discover what history and research can tell us about this fascinating dinosaur from the Late Cretaceous.

Parksosaurus Key Facts

| Keyword | Fact |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | PARKS-oh-SORE-us |

| Meaning of name | Parks’s lizard |

| Group | Ornithopod |

| Type Species | Parksosaurus warreni |

| Diet | Herbivore |

| When it Lived | 70.6 to 66.0 MYA |

| Period | Late Cretaceous |

| Epoch | Early/Lower Maastrichtian |

| Length | 6.5 to 8.2 feet |

| Height | 5.9 feet |

| Weight | 100 to 150 lbs |

| Mobility | Moved on two legs |

| First Discovery | 1922 by William Parks |

| Location of first find | Alberta, Canada |

| First Described by | 1922 by William Parks |

| Holotype | ROM 804 |

Parksosaurus Origins, Taxonomy and Timeline

The name Parksosaurus, meaning “Parks’s lizard,” is a tribute to William Parks in honor of his discovery of the fossils. The etymology combines Parks’s name with the Greek word ‘sauros,’ meaning reptile or lizard.

This dinosaur falls into the Ornithopod group, specifically within the Hypsilophodontid family. This classification places it within a group of small to medium-sized herbivorous dinosaurs known for their agility and bipedal locomotion. The genus contains only the type species, Parksosaurus warreni. The specific name honors the woman who financially supported its research, H. D. Warren.

It lived during the Late Cretaceous Period, specifically in the Early/Lower Maastrichtian Epoch. This places its existence right at the end of the Age of Dinosaurs, a time of considerable change when the world was vastly different from what we know today.

Listen to Pronunciation

For those curious about the correct pronunciation of Parksosaurus you can listen here.

Discovery & Fossil Evidence

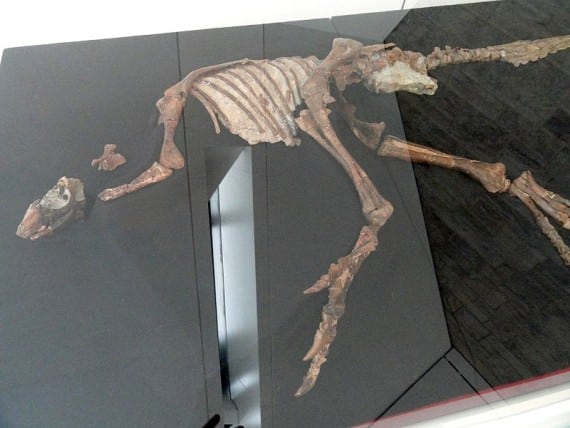

This journey of discovery and classification is as intriguing as the dinosaur itself. Initially, paleontologist William Parks described the skeleton ROM 804 as Thescelosaurus warreni in 1926. This specimen was unearthed near Rumsey Ferry on the Red Deer River. It was notable for its partial skull, still missing the beak region, and a unique skeletal composition. Among its remains were parts of the left pectoral girdle, including a suprascapula—a bone more commonly found in lizards. This discovery suggested that some Ornithopods might have had this bone in a cartilaginous form that would not preserve well in the fossil record.

The classification of this dinosaur underwent significant changes over time. Charles Sternberg, upon discovering a specimen he named Thescelosaurus edmontonensis, revisited T. warreni and concluded that it deserved its own genus. In 1940, he presented a thorough comparison of numerous differences between the two genera. This led to the establishment of Parksosaurus, initially placed in the group Hypsilophodontinae with Hypsilophodon and Dysalotosaurus. The genus then entered a period of relative obscurity until the 1970s when Peter Galton began his revision of Hypsilophodonts, leading to a redescription of Parksosaurus.

Parksosaurus Size and Description

Description of Parksosaurus

This dinosaur was one of a few non-hadrosaurid dinosaurs in the Ornithopod group that survived into the Late Cretaceous. As such, it was a small, bipedal herbivore that would have used its agile hind limbs to dart through the foliage of prehistoric Canada. Its beaklike mouth would have allowed it to feed on these plants efficiently. Let’s take a closer look at this fascinating herbivore.

Size and Weight of Type Species

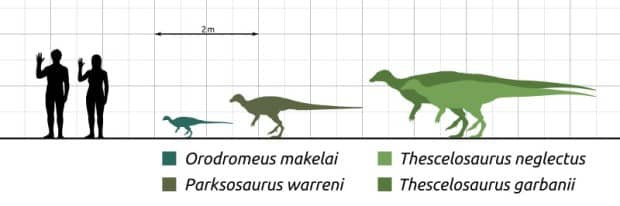

William Parks noted that the hindlimb of T. warreni was roughly the same length as that of Thescelosaurus neglectus, despite proportional differences. This suggests that Parksosaurus was around 3.3 ft tall at hips and 6.5 to 8.2 ft long. However, due to its proportional differences, such as less weight concentrated near the thigh, it was likely lighter than Thescelosaurus. These size estimates not only provide a clearer picture of this dinosaur’s physical stature but also offer insights into its locomotion and lifestyle. Estimates of its size have varied, but in 2010, Gregory Paul estimated its length at 8.2 ft and its weight at around 100.0 lbs.

The Dinosaur in Detail

Its skeletal structure was robust, particularly in the shoulder girdle. This herbivorous dinosaur had at least eighteen teeth in the maxilla and about twenty in the lower jaw, although the exact number in the premaxilla remains unknown. It also had thin, partly ossified cartilaginous plates along the ribs, a feature it shared with Thescelosaurus. Its front limbs were short but strong and may have been used for something such as burrowing or digging. The long toes of the hind limbs might have allowed it to walk over clay and mud near rivers.These physical characteristics not only give us a glimpse into its appearance but also hint at its adaptability and survival strategies.

Interesting Points about Parksosaurus

- After it was given its own genus, it was named in honor of its discoverer, William Parks.

- Despite its modest size, its bipedal locomotion suggests it was agile and swift.

- The limited fossil record makes each discovery a significant addition to our understanding.

- This herbivore used both a beaklike snout and teeth to process its food.

The Parksosaurus in its Natural Habitat

Imagine the world of Parksosaurus – a Canadian landscape marked by diverse vegetation, a climate that supported a rich ecosystem, and a geography that was both challenging and changing. This herbivore thrived in this environment, feeding on the abundant plant life. Its bipedal locomotion suggests it could navigate this terrain with ease, whether foraging for food or evading predators.

Its role in its ecosystem was significant. As a plant-eater, it not only shaped the landscape through its feeding habits but also likely played a part in seed dispersal. Its social behavior, whether as a solitary wanderer or a herd member, would have influenced its interactions with both flora and fauna.

Contemporary Dinosaurs

At the end of the Cretaceous, the two paleocontinents of Appalachia and Laramidia joined to form the more familiar North America. It was here that the nimble Parksosaurus navigated a landscape teeming with both opportunity and peril. Picture this sprightly herbivore darting through the underbrush, its lithe form a stark contrast to the lumbering giants it shared its world with.

Among these giants was the Edmontosaurus, a behemoth that towered over our main character. It resembled a bus in size compared to Parksosaurus’ much smaller stature. While the Edmontosaurus peacefully munched on high foliage, Parksosaurus feasted on lower vegetation. This illustrated a harmonious coexistence where competition for food was cleverly sidestepped.

But life for Parksosaurus wasn’t all serene grazing. Lurking in the shadows were predators like Dromaeosaurus, a fierce carnivore that could have seen our main dinosaur as a potential snack. Imagine the heart-pounding chases as the swift Parksosaurus relied on its agility to dodge the deadly embrace of its larger, menacing contemporary. These encounters were a dance of survival that showcased the predator-prey dynamics that kept the ecosystem in a delicate balance.

Then there was the cunning Troodon, roughly the same size as Parksosaurus, but a meat-eater with a taste for variety. The interactions between these two could have ranged from indifferent coexistence to tense standoffs. Perhaps Parksosaurus had to be constantly vigilant, its senses tuned to detect any stealthy approach from this intelligent hunter.

In this ancient world, Parksosaurus wasn’t just a passive participant; it was an active player in a complex web of relationships. Its life was a tapestry woven with threads of competition, cooperation, and coexistence. Each interaction, whether with the towering Edmontosaurus, the fearsome Dromaeosaurus, or the crafty Troodon, added depth to its existence and painted a vivid picture of the dynamic ecosystem it called home.

Frequently Asked Questions

It was discovered in 1922 by William Parks.

It is an Ornithopod, specifically a Hypsilophodontid.

It was an herbivore that used its teeth and beak to feed on plants.

The first fossils were found in Alberta, Canada near the Red Deer River.

It moved on its two hind legs, indicating agility and speed.

It lived during the Late Cretaceous Period around 70.6 to 66.0 million years ago.

Sources

The information in this article is based on various sources, drawing on scientific research, fossil evidence, and expert analysis. The aim is to provide a comprehensive and accurate overview of Parksosaurus. However, please be aware that our understanding of dinosaurs and their world is constantly evolving as new discoveries are made.

- https://eurekamag.com/research/025/983/025983076.php

- https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/journal-of-paleontology/article/new-smallbodied-ornithopods-dinosauria-neornithischia-from-the-early-cretaceous-wonthaggi-formation-strzelecki-group-of-the-australianantarctic-rift-system-with-revision-of-qantassaurus-intrepidus-rich-and-vickersrich-1999/D6FEF2CD3EC1CAAD8F41B6ED73EC356C

- https://www.biodiversitylibrary.org/part/52399

This article was last fact-checked: Joey Arboleda, 11-03-2023

Featured Image Credit: I, Steveoc 86, CC BY-SA 3.0 https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0/, via Wikimedia Commons