Found in the ancient rocks of southeastern Mongolia, Khankhuuluu mongoliensis offers a rare glimpse into the mid-stage evolution of tyrannosauroids. This theropod, affectionately dubbed the “Dragon Prince,” bridges the evolutionary gap between early, small-bodied tyrannosaurs and the enormous apex predators of the end-Cretaceous like Tyrannosaurus rex. Its discovery helps clarify how body size, skull structure, and developmental patterns evolved within this iconic dinosaur group.

The fossil remains of this carnivorous dinosaur, unearthed in the early 1970s and formally described only recently, reveal an animal with a distinctly gracile form. Its lightly built skeleton offers valuable insight into tyrannosauroid evolution, particularly the interplay between accelerated growth (peramorphosis) and the retention of juvenile traits (paedomorphosis). Khankhuuluu lived in a dynamic ecosystem, sharing its world with a variety of other dinosaurs, each carving out its own ecological niche.

Khankhuuluu Key Facts

| Keyword | Fact |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | KHANG-khoo-loo |

| Meaning of name | Dragon Prince |

| Group | Theropoda |

| Type Species | Khankhuuluu mongoliensis |

| Diet | Carnivore |

| When it Lived | Around 90 to 84 MYA |

| Period | Late Cretaceous |

| Epoch | Late Turonian to Santonian |

| Length | 13.1 feet |

| Height | 6.6 feet |

| Weight | 1,650.0 pounds |

| Mobility | Moved on two legs |

| First Discovery | 1972 to 1973 by Altangerel Perle |

| Described by | 2025 by Jared T. Voris, Darla K. Zelenitsky, Yoshitsugu Kobayashi, Sean P. Modesto, François Therrien, Hiroki Tsutsumi, Tsogtbaatar Chinzorig & Khishigjav Tsogtbaatar |

| Holotype | MPC-D 100/50 |

| Location of first find | Bayanshiree Formation, Mongolia |

Khankhuuluu Origins, Taxonomy and Timeline

The name Khankhuuluu carries a regal and mythical quality, quite fitting for a dinosaur of its stature. The genus name comes from the Mongolian words “khankhuu” meaning prince, and “luu” meaning dragon. Together, they form a poetic title: “Dragon Prince.” This name not only reflects its cultural roots but also evokes the creature’s striking and enigmatic presence in the fossil record.

Khankhuuluu is a member of the theropod dinosaurs, specifically within the tyrannosauroid group—a lineage that includes both the massive, iconic tyrannosaurids and their earlier, more gracile relatives. The type and only known species, Khankhuuluu mongoliensis, is currently the sole representative of its genus, with no subspecies identified to date.

This dinosaur lived during the Late Cretaceous, specifically from the late Turonian to the end of the Santonian Stage—roughly between 90 and 84 million years ago. This interval marked a pivotal phase in tyrannosauroid evolution, as the group transitioned from smaller-bodied ancestors to the larger, more specialized predators of the Late Cretaceous. Khankhuuluu represents one of the last known “mid-grade” tyrannosauroids before the emergence of the more derived Eutyrannosauria (“true tyrannosaurs”) clade.

Discovery & Fossil Evidence

The remains of Khankhuuluu were discovered during fieldwork in southeastern Mongolia in the early 1970s. Two partial skeletons were recovered from the Bayanshiree Formation at a locality known as Baishin-Tsav. Initially, these fossils were attributed to the obscure tyrannosauroid Alectrosaurus olseni, but recent reexamination of this material by Voris and colleagues revealed that they represented a distinct genus and species.

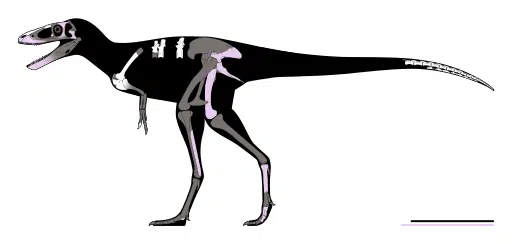

The holotype specimen, MPC-D 100/50, includes several cranial and postcranial elements, such as the nasal bone, vertebrae, a scapulocoracoid (shoulder blade), and portions of the hindlimb. A second partial skeleton, MPC-D 100/51, preserves additional skull, pelvic and hindlimb material. A third specimen, MPC-D 102/4, consisting of a frontal bone, has also been referred to the genus. While the bones are largely disarticulated, the combination of material from these three individuals has allowed researchers to reconstruct much of Khankhuuluu’s anatomy and assess its evolutionary significance.

At present, no additional specimens have been confirmed outside this locality, making these three fossils the primary basis for understanding the so-called “Dragon Prince.”

Khankhuuluu Size and Description

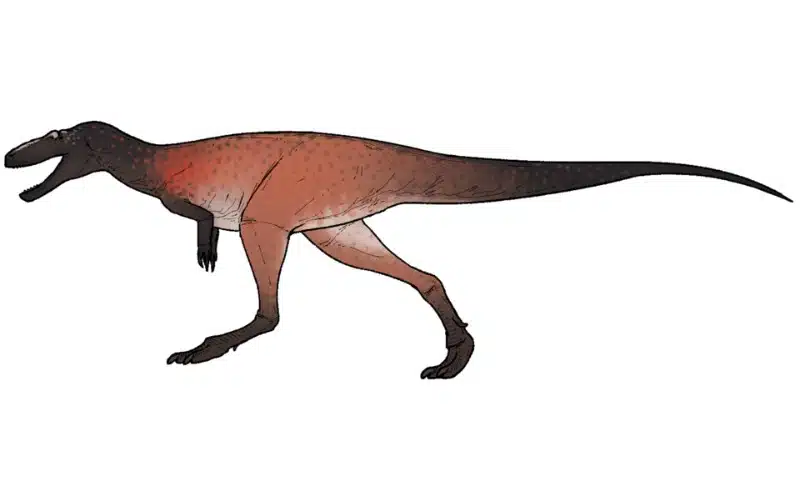

Khankhuuluu wasn’t among the giants of the dinosaur world, but its form is no less revealing. Though modest in size, it combined strength with agility. Its anatomy blends juvenile-like gracility with features typical of more derived animals, making this theropod a compelling subject for studies of growth and evolutionary trends in tyrannosauroids.

Short description of Khankhuuluu

The body of this dinosaur was balanced and gracile. It moved confidently on two legs, its relatively lightweight frame contrasting with the massive builds of later tyrannosaurids. The skull was long and shallow, and the nasal bones were ornamented with rugose surfaces and low bosses—features that may have served in display or species recognition, though they were not as prominently developed as in later, more derived tyrannosaurids.

The vertebrae along the back were tall-spined, and the tail was long, likely contributing to balance during movement. Although the forelimbs are incompletely known, the presence of a well-developed (but now lost) manual ungual and a robust scapulocoracoid suggest that the arms were functional and possibly less reduced than in later tyrannosaurids. The legs, particularly the tibiae, were long relative to the femur, indicating adaptations for swift running. The feet bore sharp claws, likely useful for gripping terrain or handling prey.

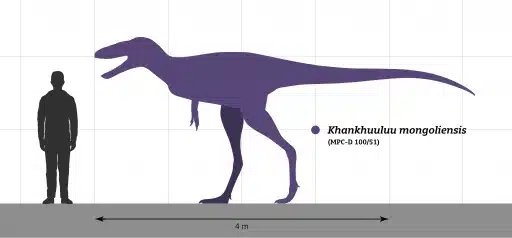

Size and Weight of Type Species

Estimates based on the preserved limb bones place the length of Khankhuuluu mongoliensis at around 13.1 feet (4 meters) from snout to tail. At the hips, it stood approximately 6.6 feet tall, making it a relatively tall dinosaur for its body mass. Its build was slender compared to later tyrannosaurids.

Weight estimates for this animal come in around 1,650.0 pounds, or roughly three-quarters of a ton. This suggests a powerful but lean predator, capable of quick bursts of speed and possibly extended pursuit of smaller prey. The long tibiae and lightweight skull further support this interpretation.

Unlike the massive bulk of Tyrannosaurus rex, this dinosaur’s proportions speak to a different ecological strategy. It was not a top predator in its environment but may have filled a more intermediate role, preying on smaller animals while avoiding competition with larger theropods or other carnivores.

The Dinosaur in Detail

What sets this dinosaur apart is not its size, but what it reveals about broader evolutionary trends within Tyrannosauroidea. In derived tyrannosaurids, the skull is often heavily ornamented, with prominent horns, bosses, and ridges around the eye socket and snout. While Khankhuuluu shows the beginnings of such features around the orbit, they are far less pronounced—lacking the upward-projected, horn-like structures seen in later forms. Its circular eye sockets, with no suborbital flange, resemble those of juvenile individuals in more derived species. Similarly, the shallow, pointed snout—a hallmark of early tyrannosauroids—was also retained during the juvenile stage in later taxa.

These anatomical signals suggest that early tyrannosauroids likely retained juvenile characteristics into adulthood—a condition known as paedomorphosis. In contrast, the exaggerated skull ornamentation and deeper snouts of advanced forms like Tyrannosaurus likely reflect peramorphosis, or accelerated and extended growth. This distinction has phylogenetic consequences: for years, taxa like Alioramus, with their shallow skulls, were often interpreted as basal (“primitive”) due to an overemphasis on cranial shape alone. However, Khankhuuluu—which lacks other derived traits present in Late Cretaceous forms like Alioramus—clarifies that shallow skulls can arise independently through different heterochronic pathways. So! – what it now looks like is that tyrannosaurid evolution was marked by widespread heterochrony, with some lineages retaining juvenile traits into adulthood while others, such as the robust tyrannosaurines, pushed cranial and postcranial development toward extreme specialisation.

The evolutionary position of Khankhuuluu is also biogeographically revealing. Phylogenetic analysis places it just outside Eutyrannosauria, the clade of large-bodied, derived tyrannosauroids that would come to dominate Late Cretaceous ecosystems. Eutyrannosaurians appear to have originated and diversified exclusively in North America, with a single dispersal event into Asia later in the Cretaceous giving rise to Alioramini and Tyrannosaurini. In this context, Khankhuuluu represents a crucial pre-dispersal lineage—an intermediate stage before the full suite of derived traits evolved. Its anatomy sheds light on how key features like skull depth, limb proportions, and body size transformed across both evolutionary time and continents.

Interesting Points about Khankhuuluu

- The name Khankhuuluu translates to “Dragon Prince,” a nod to its regal and mythical presence in Mongolian prehistory.

- For more than four decades, its fossil remains were misidentified as belonging to another species—only to be reclassified in 2025 as an entirely new genus.

- Khankhuuluu exemplifies the retention of juvenile traits into adulthood—a developmental pattern known as paedomorphosis—which appears to have played a recurring role in tyrannosauroid evolution

- Unlike its more famous cousin Tyrannosaurus rex, it had a low-profile skull and proportionally longer hindlimbs, suggesting a very different build and behavior.

- The tibiae of Khankhuuluu likely exceeded the length of its femurs, a strong anatomical clue that it was built for speed, likely capable of fast, agile movement across its environment.

Contemporary Dinosaurs

Among the dinosaurs that shared the ancient landscapes of Mongolia with the “Dragon Prince,” Gobihadros stood out as a medium-sized, plant-eating hadrosauroid – or “duck-billed dinosaur”. Likely moving in herds and browsing on low vegetation, it was a common herbivore—and a potential target for agile predators like Khankhuuluu.

Adding further herbivore diversity was Garudimimus, an ostrich-like ornithomimosaur theropod that probably supplemented its diet with plants, insects, and small animals. Its speed and omnivorous habits made it a versatile member of this dynamic ecosystem.

In contrast, large predators such as the dromaeosaur Achillobator may have occupied overlapping niches with Khankhuuluu, both relying on agility and predatory skill to capture prey. Though Achillobator was larger and more robust, these theropods likely competed directly or indirectly within their shared environment.

Heavily armored herbivores like Talarurus added further complexity to the ecosystem. With a squat, robust frame and bony armor covering its body, this ankylosaurid would have posed a serious challenge to all but the largest predators. Still, its juveniles or injured members may have fallen prey to opportunistic hunters navigating the delicate balance of survival.

Adding to this diversity was the dome-headed pachycephalosaur Amtocephale. This small-bodied herbivore or omnivore bore a thickened skull roof, likely used in social behaviors such as dominance displays or mating contests. Despite its modest size, Amtocephale may have occasionally fallen prey to predators like Khankhuuluu, illustrating the intricate predator-prey dynamics of this ancient ecosystem.

Khankhuuluu in its Natural Habitat

The world Khankhuuluu roamed was not the parched desert one might imagine. Southeastern Mongolia during the Late Cretaceous was a mix of floodplains, woodlands, and open habitats. Periodic water bodies nourished patches of vegetation, from ferns and cycads to conifers and early flowering plants. The climate was warm, possibly seasonal, and supported a wide array of life.

As a carnivore, this dino fed on smaller animals that thrived in the region. It likely relied on stealth and speed to catch prey, rather than brute force. With its long hindlimbs and relatively lightweight build, it could maneuver quickly through dense brush or open spaces, making it well-suited for ambush hunting or rapid pursuit.

While there is no direct evidence of pack behavior, its morphology doesn’t strongly suggest social hunting. It was probably a solitary predator, moving silently through its territory. Its senses, especially vision and smell, were likely acute, aiding in hunting and territory navigation. Through its interactions with prey and competitors, it helped maintain balance in its ecosystem, possibly influencing the behavior and evolution of species around it.

Frequently Asked Questions

The name means “Dragon Prince,” from the Latinized Mongolian words for prince (khankhuu) and dragon (luu).

Khankhuuluu was about 13.1 feet long and stood 6.6 feet tall at the hips. It weighed roughly 1,650 pounds.

This dinosaur lived between 93.9 and 83.6 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous.

It was first found in southeastern Mongolia, in the Bayanshiree Formation, between 1972 and 1973.

Khankhuuluu was a two-legged, meat-eating theropod and a member of the tyrannosauroid group.

Not directly, but it was closely related to the ancestors of larger tyrannosaurids and sheds light on how they developed.

Sources

The information in this article is based on various sources, drawing on scientific research, fossil evidence, and expert analysis. The aim is to provide a comprehensive and accurate overview of Khankhuuluu. However, please be aware that our understanding of dinosaurs and their world is constantly evolving as new discoveries are made.

This article was last fact checked: Joey Arboleda, 04-07-2025

Featured Image Credit: Connor Ashbridge, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons

VERY GOOD!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!!

Thanks mate, appreciate it!