Nestled in the heart of the Late Cretaceous Period, Gryposaurus, or the “Hooked-nosed Lizard,” thrived as one of the more intriguing dinosaurs of its time. With a distinctively curved nasal arch, this hadrosaur roamed what is now North America, leaving behind a rich fossil record that captivates paleontologists like me =). The hooked nose of Gryposaurus is more than just a quirky physical trait; it stands as a hallmark of a creature well-adapted to its environment, contributing to its success in the Cretaceous ecosystem.

Discovered over a century ago, Gryposaurus has provided crucial insights into the evolutionary pathways of duck-billed dinosaurs. From its first unearthing in the Dinosaur Provincial Park of Alberta, Canada, to subsequent discoveries in the United States (Montana and Utah), Gryposaurus has steadily cemented its place in the annals of paleontological history. In this article, I am going to give you further details about this fantastic dino!

Gryposaurus Key Facts

| Keyword | Fact |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | Grih-poh-SAWR-us |

| Meaning of name | Hooked-nosed lizard |

| Group | Ornithopoda |

| Type Species | Gryposaurus notabilis |

| Other Species | G. alsatei, G. latidens, G. monumentensis |

| Diet | Herbivore |

| When it Lived | 83.5 to 66.0 MYA |

| Period | Late Cretaceous |

| Epoch | Santonian to Campanian |

| Length | 26.0 feet |

| Height | Approximately 8.0 feet at the hips |

| Weight | 3.3 tons |

| Mobility | Moved on all four |

| First Discovery | 1913 by George F. Sternberg |

| Described by | 1914 by Lawrence Lambe |

| Holotype | NMC 2278 |

| Location of first find | Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta Province, Canada |

| Also found in | USA |

Gryposaurus Origins, Taxonomy and Timeline

Gryposaurus, which translates to “Hooked-nosed Lizard,” derives its name from the Greek words “grypos,” meaning crooked or hook-nosed, and “sauros,” which means lizard. The name is a direct reflection of one of its most distinguishing features: the arching nasal crest. This prominent, curved snout sets Gryposaurus apart from its fellow hadrosaurids, giving it an almost bird-like profile. The etymology of Gryposaurus not only highlights its physical uniqueness but also provides a glimpse into the paleontological practices of naming species based on observable traits.

Belonging to the Ornithopoda, Gryposaurus is a hadrosaur (the duck-billed dinosaurs, due to their characteristic broad, flat beaks). Gryposaurus’s classification within the Hadrosauridae places it among a fascinating group of herbivorous dinosaurs known for their complex dental arrangements and possible social behavior. The genus Gryposaurus includes the type species G. notabilis and three other recognized species: G. alsatei, G. latidens, and G. monumentensis. These show slight variations, likely adaptations to their specific environments within the vast Cretaceous landscape.

The timeline of Gryposaurus’s existence stretches from approximately 86.3 million years ago (MYA) to 72.1 MYA (Santonian to Campanian, late Cretaceous). This timeframe situates Gryposaurus in a world teeming with other large herbivores and predatory dinosaurs, a period characterized by warm climates and fluctuating sea levels. The Cretaceous was the last era of the Mesozoic, just before the mass extinction event that would mark the end of the non-avian dinosaurs.

Discovery & Fossil Evidence

The first discovery of Gryposaurus occurred in 1913, when George F. Sternberg, an American paleontologist, unearthed a significant fossil along the Red Deer River in Alberta, Canada, within what is now known as the Dinosaur Park Formation. This holotype specimen, cataloged as NMC 2278, included a skull and partial skeleton, featuring a distinctive nasal crest that immediately set it apart from other hadrosaurs. Canadian paleontologist Lawrence Lambe described and named Gryposaurus notabilis in 1914, drawing attention to its unusual nasal arch. This discovery provided new insights into the diversity of hadrosaurid dinosaurs and initiated further debates about its classification, especially in relation to another genus, Kritosaurus.

In the years following this initial find, additional Gryposaurus fossils were discovered across North America, particularly in the United States. For a time, the distinction between Gryposaurus and Kritosaurus was unclear, as both genera shared similar characteristics (an indeed they are sister taxa in recent phylogenies). Early discoveries, such as a partial skull collected by Barnum Brown in New Mexico, were originally attributed to Kritosaurus but lacked the complete snout, which later led to revisions and debates. By the mid-20th century, the two were often considered the same genus, a view solidified by influential publications. However, starting in the 1990s, paleontologists began to revisit these conclusions, ultimately re-establishing Gryposaurus as a distinct genus, separate from Kritosaurus and Hadrosaurus.

Other species of Gryposaurus

The discoveries of other species have expanded our understanding of the Gryposaurus genus. Notably, the species G. monumentensis was uncovered in the Grand Staircase-Escalante National Monument in Utah. This find included a well-preserved skull and partial skeleton, highlighting a more robust build and unique features like enlarged prongs on the predentary bone. Additionally, a potential new species, G. alsatei, was identified in the Javelina Formation in Texas in 2016, though further research is needed to confirm its classification. The discovery of G. monumentensis and other specimens in various locations suggests that Gryposaurus was a widespread and adaptable genus during the Late Cretaceous, thriving in diverse environments across what is now North America.

Gryposaurus Size and Description

Short description of Gryposaurus

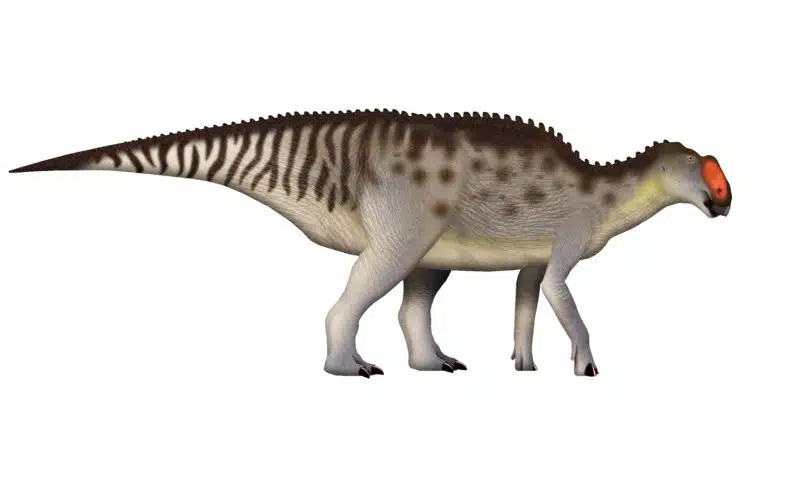

Gryposaurus was a medium-sized hadrosaurid, characterized by its robust build and distinctively curved snout. Its body was streamlined, typical of hadrosaurids, with a long, tapering tail that likely served as a counterbalance during movement. What’s cool with this dino is its prominent nasal arch, which gives it the “hooked-nose” appearance. This arch may have been used for species recognition or sexual selection, although its exact function remains a topic of debate. Gryposaurus’s neck was relatively short and muscular, connecting to a broad, rounded torso. Its limbs were sturdy, with the front limbs shorter than the hind limbs, indicating that it moved primarily on all fours but could potentially rear up on its hind legs to reach vegetation. The dinosaur’s skin was likely covered in scales, though no direct evidence of skin impressions has been definitively associated with Gryposaurus.

Size and Weight of Type Species

Gryposaurus notabilis, the type species, measured about 26.0 feet in length and stood around 8.0 feet tall at the hips. This size placed G. notabilis within the medium range for hadrosaurids, making it comparable to other members of its family. The body mass of G. notabilis is estimated to be around 3.3 tons, a weight that would have required substantial amounts of vegetation to sustain. Interestingly, while these measurements are averages based on available fossils, slight variations might have existed among individuals, particularly across different subspecies.

Size estimates for G. notabilis vary slightly depending on the source, but most agree on a general range that places it comfortably within the middle ground of hadrosaurid dimensions. Some fossil evidence suggests that certain individuals, particularly from the subspecies G. monumentensis, might have been slightly larger, hinting at possible size variation across the genus. Overall, Gryposaurus’s size made it a formidable presence in its environment, capable of fending off smaller predators and thriving in the competitive ecosystems of the Late Cretaceous.

When considering the size and weight of Gryposaurus, it’s important to remember that these estimates are based on incomplete fossil records. While the measurements provide a reasonable approximation, ongoing discoveries could refine our understanding of this dinosaur’s physical characteristics. The relatively large size and weight would have played a crucial role in its survival, enabling it to access various plant types and deter potential threats in its environment.

The Dinosaur in Detail

What truly sets Gryposaurus apart from other hadrosaurids is its distinct nasal crest. This curved nasal arch likely served multiple functions, from species identification to mating displays. The shape and size of the crest might have varied between individuals, possibly indicating age or sex differences, though these hypotheses are still under investigation.

Another fascinating aspect of Gryposaurus is its dental structure. Like other hadrosaurids, it possessed a complex set of teeth arranged in dental batteries (hundreds of teeth, organized into tightly packed rows), designed for grinding tough vegetation (It’s so cool right! I love hadrosaurids for this structure). This adaptation was crucial for a herbivore of its size, as it needed to consume vast amounts of food to sustain its energy needs. The teeth were continually replaced throughout the dinosaur’s life, allowing Gryposaurus to maintain its ability to process large quantities of plant material effectively, at any time of its life. This was a really efficient feeding mechanism for hadrosaurids, and probably helped them to thrive at their time.

The skeletal structure of Gryposaurus is also intriguing. The robust limbs and flexible joints suggest that while it was primarily quadrupedal (like others of his kind, check the work I wrote on Iguanodon). Its long, muscular tail would have provided balance while moving on all fours or rearing up on its hind legs. The overall build of Gryposaurus indicates a dinosaur well-equipped to navigate its environment, whether grazing on low-lying plants or foraging among taller vegetation.

Contemporary Dinosaurs

During the Late Cretaceous Period, Gryposaurus shared its environment with Corythosaurus, another duck-billed dino (nickname for the hadrosaurs). Corythosaurus is distinguished by its helmet-like crest, a stark contrast to the nasal arch of Gryposaurus. This crest maybe played a role in social interactions, such as communication or mating displays (hypotheses). Both dinosaurs roamed the same coastal plains, rich in vegetation. However, they likely fed on different types of plants, with Gryposaurus possibly favoring tougher, more fibrous vegetation. At the same time, Corythosaurus may have preferred softer plants, allowing them to coexist without direct competition.

Parasaurolophus, another contemporary of Gryposaurus, is renowned for its elongated, backward-curving crest (yes another duck-billed dino with a weird head). This distinctive feature may have served various functions, including sound production, temperature regulation, or social signalling (still debated). Parasaurolophus and Gryposaurus shared overlapping territories, navigating the complex social dynamics of their environment. Despite potentially competing for similar resources, they might have had different feeding strategies.

Coexisting with Lambeosaurus and Edmontosaurus

Then there was Lambeosaurus, known for its hollow, hatchet-shaped crest (another duck-billed weirdo, they are thriving at the end of the Cretaceous Period). This crest would develop during ontogeny, and males and females might display a different shape (this is a case of sexual dimorphism, see below). Lambeosaurus shared similar dietary preferences with Gryposaurus, feeding primarily on conifers, ferns, and other Cretaceous plants. The presence of these different hadrosaurid species within the same environment underscores the adaptability and evolutionary success of this group, with each species developing unique traits that allow them to coexist and thrive in a dynamic and diverse ecosystem.

In addition to these crested fellows, Gryposaurus also lived alongside Edmontosaurus, a more generalist herbivore without prominent cranial crests (but also a hadrosaurid). Edmontosaurus likely had a broader diet, enabling it to exploit a wider range of food sources within the same habitat, reducing direct competition with Gryposaurus. This dietary flexibility allowed Edmontosaurus to thrive alongside its more specialized contemporaries, showcasing the diversity of feeding strategies among hadrosaurids.

Interesting Points about Gryposaurus

- Gryposaurus’s distinctive nasal arch is one of the most unique features among hadrosaurids, possibly used for species recognition or social displays.

- It was first discovered in 1913 by George F. Sternberg, one of the most renowned North American fossil hunters of the early 20th century.

- Fossils of Gryposaurus have been found not only in Canada but also in the United States, indicating a widespread range during the Late Cretaceous.

- Unlike some other hadrosaurids, Gryposaurus’s crest was solid and non-hollow, differing from the crests of its contemporaries like Parasaurolophus and Lambeosaurus.

- The genus Gryposaurus includes several subspecies, each with slight variations that reflect adaptations to different environments within North America.

Gryposaurus in its Natural Habitat

During the Late Cretaceous, Gryposaurus inhabited a world vastly different from the one we know today. The climate was warm, and the landscapes were dominated by broad, riverine plains and dense forests. These environments were teeming with life, from towering conifers to lush undergrowth, providing ample food sources for large herbivores like Gryposaurus.

The dinosaur’s preference for these vegetated areas suggests it was well-adapted to a diet rich in fibrous plant material, which it could efficiently process with its complex dental batteries. The warm, humid climate would have supported a diverse range of plant species (but no grass yet), ensuring a steady food supply throughout the year.

The dinosaur’s robust build and strong limbs would have enabled it to move through thick vegetation, grazing on low-lying plants while possibly rearing up to access higher foliage. Its feeding habits, combined with its size and social behavior, suggest Gryposaurus could have lived in herds, which would have provided protection from predators and facilitated social interactions. This herd behavior is typical of hadrosaurids and likely contributed to the survival and success of the species.

The senses of Gryposaurus, particularly its sense of smell, might have been highly developed. Its large nasal cavity, associated with the distinctive nasal arch, may have played a role in enhancing its olfactory abilities, a must to find good food. Additionally, the dinosaur’s large eyes and keen vision would have been advantageous in spotting predators and navigating its environment.

Gryposaurus’s combination of physical adaptations and sensory capabilities made it a successful herbivore in the competitive ecosystems of the Late Cretaceous. Its ability to modify its surroundings, particularly through its feeding habits, might have also shaped the landscape, contributing to the ecological balance of its time.

Frequently Asked Questions

Gryposaurus means “Hooked-nosed Lizard,” derived from the Greek words “grypos” (Crooked or Hook-nosed) and “sauros” (lizard).

Gryposaurus was first discovered in 1913 by George F. Sternberg in Dinosaur Provincial Park, Alberta, Canada.

Gryposaurus measured about 26.0 feet in length, stood 8.0 feet tall at the hips, and weighed approximately 3.3 tons.

Gryposaurus was an herbivore that fed on a variety of Late Cretaceous plants, including conifers, cycads, and ferns (but not grass, grass does not exist yet at this time).

Fossils of Gryposaurus have been found in Canada and the United States, indicating a widespread distribution in nowadays North America.

Gryposaurus likely lived in herds, a common behavior among hadrosaurids, which provided protection and facilitated social interaction.

Sources

The information in this article is based on various sources, drawing on scientific research, fossil evidence, and expert analysis. The aim is to provide a comprehensive and accurate overview of Gryposaurus. However, please be aware that our understanding of dinosaurs and their world is constantly evolving as new discoveries are made.

- https://www.gbif.org/es/species/4965907

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/265078640_Cretaceous_dinosaurs_of_North_Carolina

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/258405977_New_Material_and_Phylogenetic_Position_of_Arenysaurus_ardevoli_a_Lambeosaurine_Dinosaur_from_the_Late_Maastrichtian_of_Aren_Northern_Spain

- https://digitallibrary.amnh.org/items/a64f6f7d-4410-4725-b2f8-6f3e191a1d82

- https://academic.oup.com/zoolinnean/article-abstract/159/2/435/2622978

This article was last fact checked: Joey Arboleda, 08-12-2024

Featured Image Credit: UnexpectedDinoLesson, CC BY 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons