Majungasaurus, might not be as well known as the famous Tyrannosaurus rex. However, this dinosaur has a story just as fascinating. Discovered in the rugged terrains of Madagascar, this theropod dinosaur, belonging to the abelisaurid, roamed the Earth during the Late Cretaceous Period. Its discovery not only enriched our understanding of dinosaur diversity but also provided a unique glimpse into the prehistoric ecosystems of Gondwana, the southern supercontinent.

Majungasaurus Key Facts

| Keyword | Fact |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | mah-jung-ah-SORE-us |

| Meaning of name | Majunga Lizard |

| Group | Theropoda |

| Type Species | Majungasaurus crenatissimus (syn. Majungatholus atopus) |

| Diet | Carnivore |

| When it Lived | 72.1 to 66.0 MYA |

| Period | Late Cretaceous |

| Epoch | Maastrichtian |

| Length | 18.0 to 23.0 feet |

| Height | Approximately 6.5 feet |

| Weight | 1,650.0 to 2,430.0 pounds |

| Mobility | Moved on two legs |

| First Discovery | 1896 by a French army officer |

| Described by | 1896 by Charles Depéret |

| Holotype | MNHN.MAJ 1 |

| Location of first find | Betsiboka River, Mahajanga, Madagascar |

Majungasaurus Origins, Taxonomy and Timeline

Majungasaurus, a name that echoes the ancient lands of Madagascar, is a testament to the rich and diverse world of dinosaurs. The etymology of its name, combining ‘Majunga’ (the old name of Mahajanga, the province where Majungasaurus was found) and the Greek ‘sauros’, reflects a blend of geographical and paleontological heritage.

The taxonomic classification of Majungasaurus places it firmly within the theropod group (more precisely the Abelisauridae), a category known for its bipedal and predominantly carnivorous members. As the type species Majungasaurus crenatissimus, it stands as a unique representative of its genus, showcasing specific characteristics that set it apart from its theropod cousins.

The timeline of Majungasaurus spans the Maastrichtian Epoch of the Late Cretaceous Period, approximately 72.1 to 66.0 million years ago. This era, marking the twilight of the age of dinosaurs, provides a crucial context for understanding the life and environment of Majungasaurus.

Listen to Pronunciation

For a more immersive experience, hear the correct pronunciation of Majungasaurus.

Discovery & Fossil Evidence of Majungasaurus

The Initial Findings and Taxonomic Journey

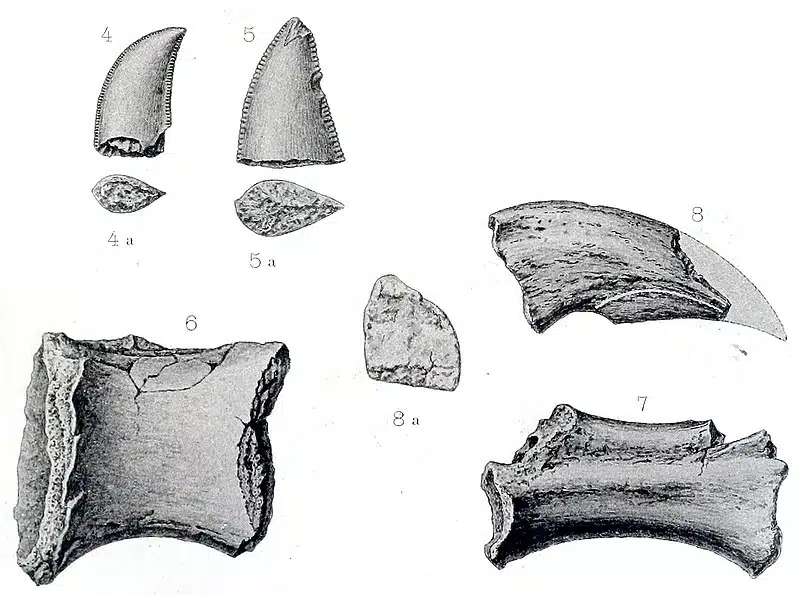

The story of Majungasaurus’ discovery begins in 1896, with French paleontologist Charles Depéret identifying the first theropod remains in northwestern Madagascar. These initial findings, comprising two teeth, a claw, and some vertebrae, were unearthed along the Betsiboka River by a French army officer. Initially, these fossils were attributed to the genus Megalosaurus, a catch-all category at the time for large theropods. The species was named M. crenatissimus, a nod to the serrated nature of the teeth.

However, Depéret later reassigned this species to the North American genus Dryptosaurus, reflecting the evolving understanding of these ancient creatures. The journey of Majungasaurus through the taxonomic landscape illustrates the complexities and challenges of classifying prehistoric life based on fragmentary evidence.

Unraveling the Mystery of Majungasaurus

Over the next century, numerous fragmented remains were collected from the Mahajanga Province, enriching the Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle in Paris. In 1955, a significant leap in understanding came when René Lavocat described a theropod dentary (jawbone) with teeth from the Maevarano Formation. This discovery was pivotal; the curved jawbone differed markedly from previously known genera like Megalosaurus and Dryptosaurus. Lavocat, therefore, established the new genus Majungasaurus, drawing from the local spelling of Mahajanga and the Greek word for lizard, ‘sauros’.

A fascinating twist occurred in 1979 when a dome-shaped skull fragment was initially classified as a new genus of Pachycephalosaur, a group known for their thick-skulled members. This classification was later revised, highlighting the dynamic nature of paleontological research.

Expanding the Majungasaurus Fossil Record

The Mahajanga Basin Project, initiated in 1993 by a team from the State University of New York at Stony Brook and the University of Antananarivo, marked a new era in the study of Majungasaurus. Led by paleontologist David W. Krause, this project unearthed a wealth of fossils, including hundreds of theropod teeth and a remarkably complete skull, which further solidified the understanding of Majungasaurus’ place in the dinosaur world.

The project’s extensive fieldwork revealed a range of specimens, from juveniles to adults, and nearly all the bones of the skeleton, though some parts remain elusive. The culmination of this work was a comprehensive 2007 monograph, detailing the biology of Majungasaurus and re-establishing the significance of the Lavocat’s dentary in defining the species. This ongoing journey of discovery underscores the ever-evolving nature of paleontology, with each find bringing us closer to understanding these magnificent creatures of the past.

- Original material described in 1896

- Mounted skeleton (cast) of Majungasaurus crenatissimus, Stony Brook University.

- Type specimen of Majungatholus atopus: a Majungasaurus frontal horn misidentified as a pachycephalosaur dome (MNHN.MAJ 1)

- Mounted skeletons of Majungasaurus and Rapetosaurus

- Mounted skeleton (cast) of Majungasaurus crenatissimus, Stony Brook University.

- Skull cast of FMNH PR 2100

- Majungasaurus crenatissimus Fossil Skull and Neck on Display at the Royal Ontario Museum (FMNH PR 2836)

- Majungasaurus in Japan

- A right dentary of a subadult Majungasaurus crenatissimus (it is the neotype), Muséum national d’histoire naturelle, Paris

Majungasaurus Size and Description

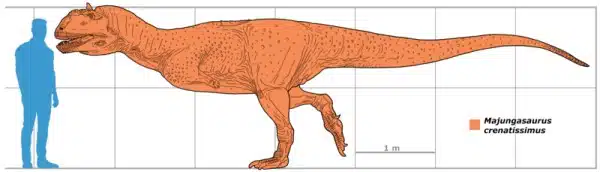

Majungasaurus, a medium-sized theropod, typically spanned a length of 18.0 to 23.0 feet and weighed between 1,650.0 to 2,430.0 pounds. Some fragmentary remains suggest that larger adults might have rivaled its relative Carnotaurus in size, potentially exceeding 26.0 feet in length. This size range positions Majungasaurus as a significant predator of its time, albeit not the largest among theropods.

Short Description of Majungasaurus

The skull of Majungasaurus is notably well-documented compared to many theropods. Similar to other abelisaurids, its skull was proportionally short for its height, measuring 24 to 28 inches in large individuals. A distinctive feature was its tall premaxilla, giving the snout a blunt appearance, typical of its family. However, Majungasaurus’ skull was wider than other abelisaurids, with a rough, sculptured texture on the skull bones, particularly pronounced on the thick, fused nasal bones with a central ridge.

A unique dome-like horn, likely covered in keratin or a similar material in life, protruded from the top of the skull. CT scans reveal hollow sinus cavities within this nasal structure and frontal horn, possibly serving to reduce the skull’s weight. The teeth, short-crowned and numerous, were characteristic of abelisaurids, with Majungasaurus bearing more teeth than most in its family.

The postcranial skeleton of Majungasaurus resembled that of Carnotaurus and Aucasaurus, other well-known abelisaurids. It was bipedal, with a long tail balancing the head and torso over the hips. The cervical vertebrae were robust yet lightened by cavities, supporting a strong, muscular neck. The humerus was short and curved, and the forelimbs were notably short with four reduced digits, indicating limited mobility and possibly lacking claws. This skeletal structure underlines Majungasaurus’ adaptation as a powerful predator, capable of swift and agile movements despite its size.

Majungasaurus: A Unique Predator in Detail

Predatory Habits and Skull Adaptations

Majungasaurus, with its distinct skull shape, stands apart from other theropods. Unlike the long, narrow skulls typical of many theropods, adept at withstanding vertical stress from powerful bites, Majungasaurus and its Abelisaurid kin boasted taller, wider, and often shorter skulls. This unique structure suggests a different predatory strategy, akin to modern felids—delivering a singular, decisive bite and holding on until the prey is subdued.

The robustness of Majungasaurus’ neck, with its interlocking ribs, ossified tendons, and reinforced muscle attachment sites, further supports this bite-and-hold hypothesis. The dinosaur’s skull was fortified by mineralized bone, creating a rough texture, particularly on the thick, fused nasal bones. The lower jaw, featuring a large fenestra and flexible joints, was likely an adaptation to prevent fractures while grappling with struggling prey. The front teeth, robust and designed for anchoring, along with the unique tooth shape—curved at the front but straighter at the back—suggest a mechanism for holding rather than slicing.

Cannibalistic Tendencies

Intriguingly, evidence points to Majungasaurus practicing cannibalism. Fossils bearing tooth marks matching its bite, suggest it fed on members of its own species. This behavior, confirmed in no other non-avian Theropod, raises questions about whether this was active hunting or scavenging. The behavior of modern Komodo monitors, which sometimes cannibalize rivals, offers a potential parallel.

Respiratory System Insights

The respiratory system of Majungasaurus, inferred from well-preserved vertebrae, suggests the presence of avian-style lungs and air sacs. This efficient, flow-through ventilation system, similar to that of birds, indicates a shared evolutionary path predating the divergence of the ceratosaur and tetanuran lines.

Brain and Inner Ear Structure

CT scans of Majungasaurus skulls have allowed for reconstructions of its brain and inner ear. The small brain, relative to body size, and a smaller flocculus region suggest Majungasaurus did not rely on quick head movements for hunting. The structure of its inner ear, particularly the longer lateral semicircular canal, indicates a sensitivity to side-to-side head motions, differing from many other theropods.

Pathologies and Growth Patterns

Studies of Majungasaurus fossils have revealed various pathologies, including healed injuries and abnormal bone growths, particularly in the vertebrae. These findings suggest a life marked by physical challenges and adaptations. Additionally, research indicates that Majungasaurus experienced slow growth, taking around twenty years to reach maturity, a trait possibly influenced by its harsh environment.

In summary, Majungasaurus, with its unique adaptations and behaviors, offers a fascinating glimpse into the life of a dominant predator in its ecosystem. Its study not only enriches our understanding of theropod diversity but also sheds light on the evolutionary pathways shared among dinosaurs.

Contemporary Dinosaurs

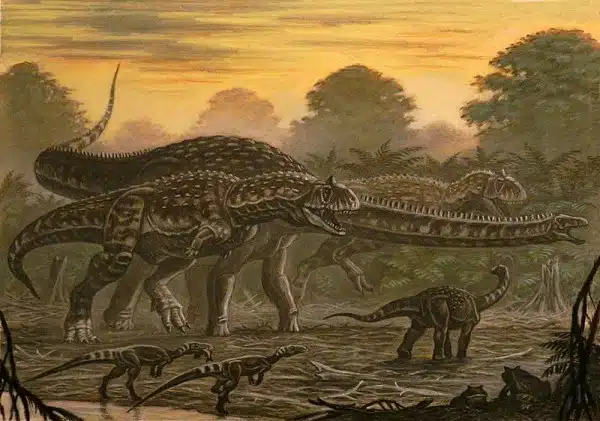

In the late Cretaceous Period, the fierce Majungasaurus roamed the ancient landscapes, a true titan among its contemporaries. Imagine a world where the air buzzed with the calls of Rahonavis, a creature smaller than Majungasaurus, with the grace of a bird but the heart of a raptor. These two shared a complex dance of predator and prey. Majungasaurus, with its powerful jaws and muscular build, might have eyed the nimble Rahonavis as a challenging yet appetizing target. The skies and the land intertwined in this ancient drama, where the lumbering steps of Majungasaurus sent shivers through the underbrush, alerting the watchful Rahonavis.

In this prehistoric tableau, Masiakasaurus made its presence known, its peculiar, forward-jutting teeth a stark contrast to the robust bite of Majungasaurus. Smaller in size, Masiakasaurus was likely not a direct competitor but rather a crafty co-inhabitant, picking at what Majungasaurus left behind. This dynamic painted a vivid picture of coexistence and opportunism. While Majungasaurus dominated as a top predator, Masiakasaurus thrived in the margins, perhaps scavenging the remains left by other dinosaurs. Possibly darting in to snatch smaller prey, ensuring a delicate balance in this ancient ecosystem.

Rapetosaurs Another Contemporary

Then there was Rapetosaurus, a gentle giant, towering and massive, a stark contrast to the more compact and ferocious Majungasaurus. Their paths might have crossed less as competitors and more as indifferent neighbors, each commanding their own niche. Majungasaurus, unlikely to challenge such a massive creature, might have watched from a respectful distance as Rapetosaurus ambled through. The herbovire busy stripping leaves from the high branches, a serene colossus in a world of tooth and claw. In this prehistoric drama, each character, from the agile Rahonavis to the towering Rapetosaurus, played a role that highlighted the might and majesty of Majungasaurus, a dominant predator in a world of diverse and fascinating creatures.

Interesting Points about Majungasaurus

- Majungasaurus is one of the few dinosaurs known to have lived on the island of Madagascar, offering a unique perspective on dinosaur diversity and distribution.

- The distinct shape of its teeth and jaws suggests specialized feeding habits, possibly including scavenging.

- Its robust build and bipedal locomotion indicate a powerful and agile predator.

- The study of Majungasaurus fossils has provided insights into the Late Cretaceous ecosystems of Gondwana.

- The discovery and analysis of Majungasaurus remains have played a crucial role in understanding the evolution and diversity of theropod dinosaurs.

Majungasaurus in its Natural Habitat

The Maevarano Formation: A Window into the Past

Majungasaurus’ story is intricately tied to the Maevarano Formation in the Mahajanga Province of northwestern Madagascar. This geological formation, comprise the Anembalemba, Masorobe, and Miadana Members. It provides a rich tapestry of the Maastrichtian Stage, dating from 70.0 to 66.0 million years ago. The presence of Majungasaurus teeth up until the end of this period marks it as a survivor. It lived until the very twilight of the non-avian dinosaurs.

Madagascar’s Ancient Landscape

During the time of Majungasaurus, Madagascar was already an island, having separated from the Indian subcontinent less than 20 million years prior. Drifting northward, it was positioned more southerly than its current location. The climate was semi-arid with distinct seasonal variations in temperature and rainfall. Majungasaurus roamed a coastal floodplain, crisscrossed by sandy river channels. The geological evidence suggests periodic debris flows, especially at the onset of the wet season, which likely contributed to the exceptional preservation of many fossils.

A Dynamic Ecosystem

The ecosystem of the Maevarano Formation was diverse and vibrant. In addition to Majungasaurus, it was home to a variety of species: fish, amphibians like frogs, reptiles including lizards and snakes, and an impressive array of crocodylomorphs—seven distinct species. Mammals, birds like Vorona, and the Dromaeosaurid Rahonavis, which might have been capable of flight, added to the diversity. The presence of the Noasaurid Masiakasaurus and two titanosaurian Sauropods, including Rapetosaurus, paints a picture of a rich and varied food web.

The Apex Predator

Majungasaurus stood as the largest carnivore and likely the apex predator on land in this environment. Its dominance was challenged only near water sources by large Crocodylomorphs such as Mahajangasuchus and Trematochampsa. This dynamic interplay of species in the Maevarano Formation offers a glimpse into a complex ecosystem. There it played a crucial role, not just as a predator but also as a shaping force in its environment.

The natural habitat of Majungasaurus was a semi-arid, coastal floodplain with a diverse array of species. This setting provided the backdrop for the life and reign of one of the last great non-avian dinosaurs. Offering invaluable insights into the ecosystems of the Late Cretaceous Period.

Frequently Asked Questions

Majungasaurus was first discovered in 1896 near the Betsiboka River in Mahajanga, Madagascar.

Majungasaurus is a theropod dinosaur, belonging to the Abelisauridae.

As a carnivore, Majungasaurus likely preyed on other animals and possibly scavenged.

Majungasaurus lived approximately 72.1 to 66.0 million years ago during the Late Cretaceous Period (Maastrichtian).

The fossils of Majungasaurus were primarily found in Madagascar, near the Betsiboka River in Mahajanga.

Majungasaurus is unique for its robust build, specialized teeth and jaws. This made it a top predator in the Late Cretaceous ecosystems of Madagascar.

Sources

The information in this article is based on various sources, drawing on scientific research, fossil evidence, and expert analysis. The aim is to provide a comprehensive and accurate overview of Majungasaurus. However, please be aware that our understanding of dinosaurs and their world is constantly evolving as new discoveries are made.

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/230808684_Overview_of_the_history_of_discovery_taxonomy_phylogeny_and_biogeography_of_Majungasaurus_crenatissimus_Theropoda_Abelisauridae_from_the_Late_Cretaceous_of_Madagascar

- https://www.jstor.org/stable/4523759

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1671/0272-4634%282007%2927%5B1%3AOOTHOD%5D2.0.CO%3B2

Article last fact-checked: Joey Arboleda, 01-06-2024

Featured Image Credit: Primeval Artist, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons