In the ancient landscapes of southern Africa, a colossal herbivore roamed the Early Jurassic floodplains. Known as Ledumahadi, this dinosaur’s name translates to “Giant Thunderclap,” a poetic nod to both its massive size and the cultural heritage of the region. As possibly the largest land-animal of its time, this dinosaur provides fascinating insights into a critical period of sauropodomorph evolution, bridging the gap between smaller ancestral forms and the enormous giants that dominated later eras.

Fossils of this remarkable creature reveal a blend of primitive and advanced features, underscoring its transitional role in dinosaur evolution. With a body built for consuming as much high-and-low growing vegetation as it could reach, Ledumahadi would have left a profound impact on its ecosystem. Let’s delve deeper into the story of this “Giant Thunderclap.”

Ledumahadi Key Facts

| Keyword | Fact |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | Leh-doo-mah-hah-dee |

| Meaning of name | Giant Thunderclap |

| Group | Basal Sauropodomorpha |

| Type Species | Ledumahadi mafube |

| Diet | Herbivore |

| When it Lived | 201.3 to 190.8 MYA |

| Period | Early Jurassic |

| Epoch | Hettangian to Sinemurian |

| Length | Approximately 31.2 feet |

| Height | 6.6 feet at the hips |

| Weight | 13.0 tons |

| Mobility | Moved on all fours (quadrupedal) |

| First Discovery | 1990s by James Kitching |

| Described by | 2018 by Blair McPhee, Roger Benson, Jennifer Botha-Brink, Emese Bordy, and Jonah Choiniere |

| Holotype | BP/1/7120 |

| Location of first find | Beginsel Farm, Free State Province, South Africa |

Ledumahadi Origins, Taxonomy, and Timeline

The name Ledumahadi is derived from the Southern Sotho language, translating to “A Giant Thunderclap.” This evocative name not only honors the dinosaur’s immense size but also reflects its discovery within a cultural context. The species name, mafube, means “at dawn,” emphasizing the dawn of giant herbivores in the Early Jurassic. This poetic naming bridges science and cultural heritage, grounding the discovery in its regional and historical significance. The thunderous imagery aptly conveys the impact this dinosaur must have had on its environment.

Ledumahadi belongs to the lessemsaurid family, a group of sauropodiform dinosaurs that appeared to represent an early “attempt” at sauropod-like gigantism while still largely retaining a primitive, “prosauropod”-like body plan (more on that below). As such, Ledumahadi offers invaluable insights into the range of adaptive strategies these burgeoning giants were exploring at the outset of the Jurassic 200 million years ago.

Specifically hailing from the Hettangian to the Sinemurian Epochs of the Early Jurassic – approximately 201.3 to 190.8 million years ago – this era followed the Triassic-Jurassic extinction event, a time of ecological recovery and diversification. Ledumahadi emerged as a dominant herbivore during this period, shaping and being shaped by its dynamic environment.

Discovery & Fossil Evidence

The first fossils of Ledumahadi were unearthed in the 1990s on Beginsel Farm, located in South Africa’s Free State Province. These remains were initially collected by the famed South African fossil hunter James Kitching during a survey for the Lesotho Highland Waters Project. Two decades later, intrigued by the size of these remains collecting dust in the university collections, Witwatersrand palaeontologist Adam Yates managed to relocate the find spot. To his happy surprise there were “fresh” fossils eroding out of the hillside!

The last of these remains were exhumed by a team from the University of the Witwatersrand between 2012 and 2015, and in 2018, a team led by myself, alongside Roger Benson, Jennifer Botha-Brink, Emese Bordy, and Jonah Choiniere, officially named and described the dinosaur. The holotype specimen, cataloged as BP/1/7120, includes several well-preserved bones that provide invaluable insights into its anatomy and lifestyle.

The remains consist of several important pieces, including parts of its backbone, such as a partial cervical neural arch, several dorsal vertebrae, and some sacral and caudal (tail) vertebrae. Other notable finds include parts of its forelimb such as a right ulna, as well as portions of its hindlimbs, including the distal end of a right femur and a big toe ungual (claw).

This collection of bones, while disarticulated, provides enough detail for paleontologists to form a fair picture of its structure and adaptations. These fossils show that Ledumahadi was a (mostly) quadrupedal dinosaur with robust limbs capable of supporting its massive body. The excellent preservation of these remains has allowed researchers to reconstruct its anatomy and evolutionary significance with remarkable clarity.

Ledumahadi Size and Description

Short Description of Ledumahadi

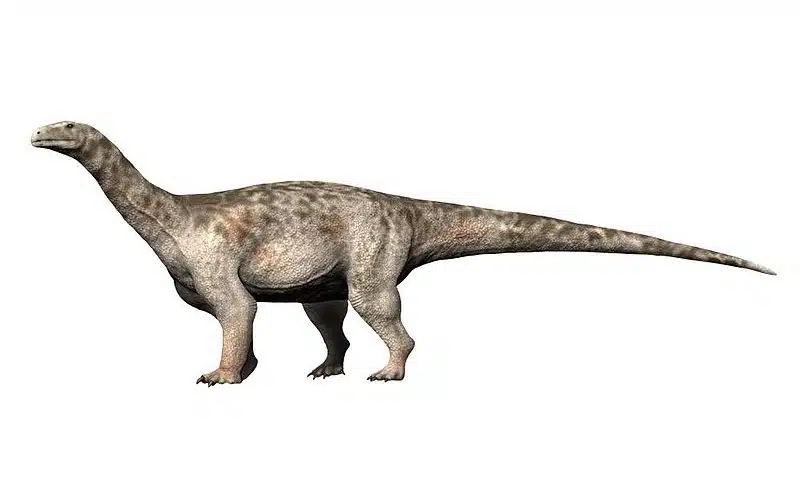

Ledumahadi was a massive herbivore with a robust, muscular build. Its body was supported by powerful, robust limbs that were more squat in general proportions to the columnar forelimbs of later sauropods. A relatively short neck further set it apart from the long-necked giants that followed, while its tail likely served as a counterbalance during movement. Its skin, though not directly preserved, is thought to have been thick and protective, similar to other large dinosaurs.

The dinosaur’s quadrupedal gait was a significant evolutionary step, as earlier relatives were primarily bipedal. This shift likely allowed it to bear greater weight, enabling its impressive size.

Size and Weight of Type Species

Ledumahadi measured approximately 31.2 feet in length and stood 6.6 feet tall at the hips, making it one of the largest dinosaurs of its time. Its estimated weight of 13.0 tons places it firmly among the early giants. These dimensions suggest a creature that dominated its environment, both in size and ecological influence.

Unlike later sauropods, which achieved even greater lengths and weights, Ledumahadi’s build reflects a transitional stage. Its size hints at the evolutionary pressures that would eventually lead to the colossal proportions seen in later species.

The Dinosaur in Detail

Initially, the great size of Ledumahadi made its discoverers wonder if they hadn’t stumbled upon the world’s largest ever bipedal animal. This is because the ulna – one of the first collected bones – looked like that of a blown-up “propsauropod” (the old, informal name for non-sauropod sauropodomorphs or basal Sauropodomorpha, which were typically bipedal). In contrast, the forelimbs of quadrupedal sauropods are relatively elongate.

This is due to sauropods having evolved what we call the “parasagittal” condition. Like most modern mammals today (well, the larger, quadrupedal ones), this means that the limbs are oriented directly below the body in the form of a columnar support strut with limited lateral flexion. The advantage of this condition is that weight is distributed much more efficiently and safely at larger body sizes.

Instead, Ledumahadi appeared to retain the laterally-flexed, “elbows out” condition primitive to early dinosaurs and still seen today in living lizards and amphibians. As bipeds, this lateral flexibility was likely instrumental in manipulating objects closer to the body, be it prey or foliage.

However, as more information and bones came to light, it became clear to us that Ledumahadi had to be at least habitually quadrupedal. So why this retention of a primitive style forelimb at such a formidable (and possibly dangerous) body size?

The Pros and Cons of a Flexed Mobile Forelimb

Well, it has long been a pet theory of mine that the retention of a primitive forelimb in lessemsaurids is suggestive of their “unwillingness” to forgo the behaviour that made sauropodomorphs such successful herbivores in the first place: the ability to rear-up on the hindlegs to reach higher vegetation. In addition to helping lean against the trunks of trees, returning your multi-ton mass to earth is a heck of a lot safer with a flexed elbow than a rigid one.

Nonetheless, the retention of a flexed, mobile forelimb had its own disadvantages. Namely in placing an upper limit on how big these animals were truly allowed to get. A threshold likely embodied by Ledumahadi itself. A much more efficient form of quadrupedal gigantism came on the scene towards the end of the Early Jurassic. That was with the columnar-limbed sauropods – likely contributing to the doom of Ledumahadi and its ilk!

Contemporary Dinosaurs

The Early Jurassic landscape teemed with a variety of dinosaurs, each playing unique roles in their shared ecosystem. Among them was Aardonyx, another basal sauropodomorph. This dinosaur exhibited both bipedal and quadrupedal traits, suggesting it could adapt its walking style based on need. Smaller and more agile than Ledumahadi, Aardonyx likely focused on feeding in less competitive areas, accessing vegetation at different heights and reducing direct competition with its larger neighbor.

Another fascinating inhabitant was Lesothosaurus, a small, swift herbivore known for its agility. Unlike the massive and slow-moving Ledumahadi, Lesothosaurus relied on speed to avoid predators. It likely darted through undergrowth, feeding on low vegetation. The contrasting lifestyles and sizes of these two herbivores highlight the diversity of ecological niches occupied during this period.

Pulanesaura, another sauropodiform, coexisted with Ledumahadi and offered a complementary feeding strategy. While Ledumahadi’s robust frame and generalized feeding strategy allowed it to graze on a wider variety of vegetation, Pulanesaura likely grazed on ferns and other plants closer to the ground. As an obligate quadruped, Pulanesaura potentially represented one of the earliest known true sauropods. Together, the distinct adaptations of Ledumahadi and Pulanesaura helped maintain ecological balance and demonstrate the variety of strategies herbivores employed to thrive in this environment.

Lurking in the shadows was Dracovenator, a theropod predator and a constant threat to herbivores. While unlikely to challenge a fully grown Ledumahadi, Dracovenator might have targeted juveniles or smaller dinosaurs like Lesothosaurus. Its presence added a layer of predation pressure, influencing the behavior and group dynamics of herbivores within the ecosystem.

Together, these dinosaurs created a dynamic and interdependent community, showcasing the complexity and richness of the Early Jurassic environment.faced.

Interesting Points about Ledumahadi

- The name “Giant thunderclap” reflects both its size and its cultural significance.

- Ledumahadi represents an early experiment in sauropodomorph gigantism. Presaging but not directly leading to the unique columnar-limbed gigantism of later sauropods.

- Its robust limbs are among the earliest examples of adaptations for supporting massive weight. Ledumahadi was likely representing the upper-size threshold that quadrupeds with a laterally flexed forelimb could attain.

- The discovery site highlights South Africa’s importance in Jurassic paleontology.

- It coexisted with a variety of herbivores and predators, showcasing a dynamic Early Jurassic ecosystem.

Ledumahadi in its Natural Habitat

The landscape that Ledumahadi inhabited was predominantly arid floodplain criss-crossed by a series of braided rivers. Vegetation was concentrated most heavily around these river channels. While likely fluctuating during successive flood and drought periods, was nonetheless abundant enough to support a large community of varied herbivores. The dinosaur’s diet consisted of cycads, ferns, and other Jurassic flora, forming the foundation of its sustenance.

Its quadrupedal locomotion allowed it to move steadily across the plains, while its retained ability to safely rear on its hindlegs allowed it to browse on vegetation at various heights. Social behavior remains speculative, but it may have traveled in groups for protection against predators like Dracovenator. This social structure would have offered additional advantages, such as cooperative grazing and shared vigilance.

In shaping its ecosystem, Ledumahadi’s feeding habits likely influenced vegetation patterns. By consuming large amounts of plant material, it contributed to the cycling of nutrients. In so doing, it supported the growth of new vegetation and sustaining the broader ecosystem.

Frequently Asked Questions

The name means “Giant Thunderclap,” reflecting its size and cultural significance.

It lived during the Early Jurassic, approximately 201.3 to 190.8 million years ago.

As a herbivore, it fed on vegetation like ferns and cycads, thriving in subtropical floodplains.

It measured approximately 31.2 feet in length, stood 6.6 feet tall at the hips, and weighed about 13.0 tons. Placing it amongst the largest land animals of the earliest Jurassic.

Its fossils were found on Beginsel Farm in South Africa’s Free State Province.

It represents an early experiment in sauropodomorph gigantism. Showing that there were different ways in which the group “got big” prior to the rise of Sauropoda.

Sources

The information in this article is based on various sources, drawing on scientific research, fossil evidence, and expert analysis. The aim is to provide a comprehensive and accurate overview of Ledumahadi. However, please be aware that our understanding of dinosaurs and their world is constantly evolving as new discoveries are made.

Article last fact checked: Joey Arboleda, 12-14-2024

Featured Image Credit: Nobu Tamura, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons