Tucked into the cooler margins of Late Cretaceous North America, Leptoceratops carved out a quiet but unique niche among its ceratopsian kin. This small, hornless ceratopsian didn’t have the dramatic frills or large horns that define its more flamboyant relatives, but what it lacked in flair, it made up for in anatomical sophistication. Its skull hints at a complex, mammal-like chewing motion, and its fossils tell a story of quiet resilience amid a landscape dominated by giants.

Though first described over 100 years ago, this dinosaur continues to earn attention for its unique adaptations and anatomy. Its fossils come from varied formations across Alberta, Montana, and Wyoming, preserving not only bones but also insight into a rarely spotlighted ecological role. Unlike the hulking predators and massive sauropods of its time, this stocky herbivore kept a lower profile—both literally and ecologically.

Leptoceratops Key Facts

| Keyword | Fact |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | LEP-toh-SAIR-uh-tops |

| Meaning of name | Small Horn Face |

| Group | Cerapoda |

| Type Species | Leptoceratops gracilis |

| Diet | Herbivore |

| When it Lived | 72.2 to 66.0 MYA |

| Period | Late Cretaceous |

| Epoch | Late/Upper Maastrichtian |

| Length | 6.6 feet |

| Height | 2.6 feet |

| Weight | 220.0 pounds |

| Mobility | Moved (mostly) on all four |

| First Discovery | 1910 by American Museum of Natural History expedition |

| Described by | 1914 by Barnum Brown |

| Holotype | AMNH 5205 |

| Location of first find | Wheatland County, Alberta, Canada |

| Also found in | Montana and Wyoming, USA |

Leptoceratops Origins, Taxonomy and Timeline

The name Leptoceratops translates to “small horn face”—a fitting title, even if it was more symbolic than literal. Coined from the Greek words leptos (“slender” or “small”) and ceratops (“horn face”), the name might lead one to expect horns, yet this dinosaur’s face was notably unornamented, lacking the prominent horns that its name might suggest. Paleontologist Barnum Brown introduced the name in 1914, describing a dinosaur that, while hornless, still bore the family resemblance to its more famous ceratopsian cousins.

In the great tree of dinosaur classification, this dino belongs to the broad clade of Ceratopsia. Less inclusively it belongs to Leptoceratopsidae—a family named after it. Like other leptoceratopsids, Leptoceratops retained a low-slung, conservative body plan reminiscent of other hornless ceratopsians like Protoceratops, but the similarity reflects parallel evolution rather than direct ancestry. Leptoceratopsids evolved along a separate branch of the ceratopsian family tree, developing their own distinctive adaptations despite their primitive appearance.

Living toward the very end of the Cretaceous, Leptoceratops occupied the Maastrichtian Stage, ranging from roughly 72.2 to 66.0 million years ago. This timing placed it just before the mass extinction event that wiped out most dinosaurs. As such, it coexisted with some of the last and most diverse members of the dinosaurian world, nestled within a cool, dynamic environment of shifting rivers and flowering plants.

Discovery & Fossil Evidence

The initial fossils of Leptoceratops were discovered in 1910 along Alberta’s Red Deer River by an American Museum of Natural History expedition. Two partial skeletons were found weathering out of a cow trail, and the better-preserved individual—featuring elements of the skull, vertebrae, and limbs—was designated the holotype (AMNH 5205). Barnum Brown formally described Leptoceratops gracilis in 1914, introducing this compact ceratopsian to science.

Subsequent discoveries expanded the known material. In 1947, Canadian paleontologist Charles M. Sternberg excavated three additional skeletons from the same region, including one nearly complete specimen. Described in 1951, these finds—such as CMN 8887 and CMN 8889—helped refine understanding of its skeletal structure.

Additional fossils have been found in Montana’s Hell Creek and Two Medicine formations, as well as Wyoming’s Lance Formation. While some early material from Montana was later reclassified (e.g., Montanoceratops), the remaining specimens support a consistent picture of Leptoceratops as a small, robust herbivore. More than ten individuals are now known, representing most of the skeleton and offering rare insight into a relatively basal ceratopsian.

- Fossil of Leptoceratops at the Canadian Museum of Nature, Ottawa

- Leptoceratops gracilis forelimb.

- Skull of Leptoceratops gracillis, from the Tolman Bridge area, Alberta. On display at the Royal Tyrrell Museum, Alberta, Canada.

Leptoceratops Size and Description

Short Description of Leptoceratops

Physically, this dinosaur displayed a curious blend of ancestral and derived traits. It had a bulky body, a relatively short neck, and a large head. Unlike its more flamboyant relatives, it lacked facial horns and had a reduced frill. Its beak-like mouth, however, was backed by strong jaws filled with rows of teeth specialized for grinding tough plant material.

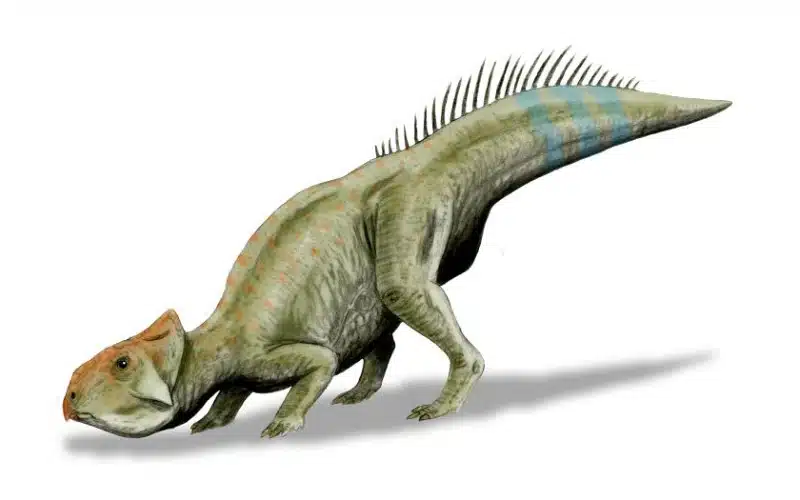

It likely walked on all fours most of the time, although studies suggest it could rise up and run bipedally when needed. Its forelimbs were built for strength, possibly aiding in digging or manipulating vegetation. The tail was long and stiff, supported by high-spined vertebrae, offering balance and possibly used for display or defense.

Size and Weight of Type Species

Measurements from several well-preserved specimens provide solid estimates of Leptoceratops’ size. Adult individuals reached about 2 m (6.6 ft) in length, stood roughly 0.8 m (2.6 ft) at the hip, and likely weighed around 100 kg (220 lb).

Size variation among specimens suggests a growth series: CMN 8887, the smallest, appears to represent a juvenile, while specimens like AMNH 5205 and YPM VPPU 18133 are among the largest known adults. These differences help deepen understanding of its growth and development.

Despite its modest size, Leptoceratops’ robust build and specialized skull allowed it to thrive amid larger herbivores and predators. Its niche—favoring agility, efficient feeding, and possibly digging behavior—gave it a competitive edge in its environment.

The Dinosaur in Detail

What sets this animal apart is its jaw. Its chewing mechanism was unusually sophisticated for a dinosaur. Its teeth show a unique pattern of wear—one that required a circular grinding motion not unlike that of mammals. This motion, called circumpalinal mastication, allowed it to process fibrous plant material with impressive efficiency.

Its skull, while structurally primitive, was notably large in proportion to its body. It featured powerful jaws and flared cheeks but lacked the elaborate horns and its frill was notably diminutive compared to more derived ceratopsians. This absence of prominent visual display structures suggests that defense or communication through ornamentation was not a major part of its behavior. Instead, Leptoceratops likely relied on more understated strategies for survival—such as efficient feeding and possibly burrowing.

Another fascinating feature is its strong forelimbs, which some researchers believe were suited for scratch-digging. This has led to the hypothesis that Leptoceratops may have excavated burrows, possibly living in small family groups within these shelters. Fossil evidence from the Hell Creek Formation supports this idea, where multiple individuals were found together, potentially representing collapsed burrows. While its hands were likely too limited in dexterity to grasp food single-handedly, it may have been able to manipulate or hold plant material using both forelimbs in coordination.

Its tail, meanwhile, featured elongated neural spines, which may have given it a tall sail, spiked, or ridge-like appearance in life. This unusual structure could have served a number of functions—providing balance, supporting powerful muscles, or even contributing to visual signaling or thermoregulation. Whatever the purpose, it likely made Leptoceratops’ tail a more prominent and dynamic part of its silhouette than in many of its close relatives.

Interesting Points about Leptoceratops

- Although its name translates to “small horn face,” this dinosaur lacked any actual horns—an ironic twist for a member of the ceratopsian group.

- Its chewing mechanism was remarkably advanced for its time, using a circular, grinding motion more commonly seen in mammals than in other dinosaurs.

- Evidence from fossil sites suggests it may have lived in multi-generational family groups within shared burrows, hinting at complex social behavior.

- Pound for pound, this small herbivore packed an impressive bite—one of the most powerful among early ceratopsians relative to its size.

- Unlike its later, bulkier relatives, it could switch between walking on four legs and rearing up on two when needed, giving it added mobility and agility.

Contemporary Dinosaurs

Leptoceratops shared its ecosystem with a number of iconic North American dinosaurs from the very end of the Cretaceous. Despite its modest size and low-slung frame, it lived among some of the most well-known giants of the Late Maastrichtian world.

Towering above most other creatures was Tyrannosaurus rex, the apex predator of its time. With its massive skull, bone-crushing bite, and keen senses, it would have posed a constant threat to nearly all animals in the region—including smaller herbivores like Leptoceratops. While a full-grown T. rex may not have routinely hunted such modest prey, juveniles or opportunistic adults could have targeted them when the opportunity arose.

Another prominent resident was Triceratops, a much larger and heavily built ceratopsian. Unlike the smaller, hornless Leptoceratops, Triceratops possessed a massive frill and three formidable facial horns, likely used in both defense and social behavior. Although the two were distantly related, their coexistence reflects the evolutionary breadth within the ceratopsian lineage.

Large hadrosaurids such as Edmontosaurus were also common. These duck-billed herbivores traveled in herds and browsed on mid-level vegetation, complementing the feeding niche of Leptoceratops, which focused on low-growing plants. This vertical partitioning of food resources helped reduce competition between herbivores of different sizes.

Pachycephalosaurus

Also inhabiting the region was its marginocephalian clade-mate Pachycephalosaurus, recognized by its thick, dome-shaped skull. This distinctive feature is thought to have been used in intraspecific behavior such as head-butting or flank-butting during contests for mates or territory. Likely bipedal and possibly omnivorous, Pachycephalosaurus occupied a different ecological niche from Leptoceratops. Feeding on a mix of low-lying plants, seeds, and perhaps small animals or insects. Despite their differences, both dinosaurs foraged close to the ground and had to remain vigilant in a landscape crowded with formidable predators. Their coexistence underscores the diversity of survival strategies within the Late Cretaceous herbivore communities.

Together, these species created a tiered and complex ecosystem. One in which Leptoceratops maintained its place not through size or strength, but through adaptability. In a world of towering predators and armored giants, it thrived as a tough, ground-level survivor. Using efficient feeding, agility, and perhaps even burrowing behavior to endure in the closing chapters of the Mesozoic era.

Leptoceratops in its Natural Habitat

The world this dinosaur called home was transitional, spanning semi-arid plains and more humid wetland environments. The landscape was shaped by braided streams, floodplains, and forests populated by conifers, cycads, and early flowering plants. These diverse plant communities supported a wide range of herbivores, from towering sauropods to small, nimble grazers.

Its diet likely consisted of tough, fibrous vegetation. Equipped with specialized teeth and a jaw adapted for grinding, it could efficiently process a variety of plant materials—from ferns and horsetails to seeds and early angiosperms. This dietary versatility may have provided a survival advantage amid shifting climatic conditions.

Behaviorally, it may have been social—if the burrowing hypothesis is correct, it probably lived in small family groups, excavating shelters in hillsides or floodplain banks. Its senses were likely well-developed, with keen eyesight and possibly acute hearing. Enabling it to detect threats in a landscape where predatory theropods were a constant presence.

Frequently Asked Questions

It inhabited floodplains and streamside forests during the Late Cretaceous, with both semi-humid and coastal habitats.

Leptoceratops could move on all fours but likely ran on two legs when needed, especially to evade predators.

There’s evidence it may have lived in family groups, possibly digging and inhabiting burrows together.

As an herbivore, it consumed low-lying plants, seeds, and possibly fibrous foliage like cycads and conifers.

It was smaller than most, reaching about 6.6 feet in length and weighing around 220.0 pounds.

Sources

The information in this article is based on various sources, drawing on scientific research, fossil evidence, and expert analysis. The aim is to provide a comprehensive and accurate overview of Leptoceratops.

Article last fact checked: Joey Arboleda, 06-06-2025

Featured Image Credit: Nobu Tamura, CC BY 3.0, via Wikimedia Commons