From the layered rocks of Patagonia’s Los Alamitos Formation emerges a lesser-known herbivore with a name as distinctive as its evolutionary lineage. Huallasaurus, a duck-billed dinosaur from Argentina, lived in a world nearing the end of the Age of Dinosaurs. Though it didn’t reach the colossal size of a long-necked sauropod, it carried with it the anatomical refinements of its group, showing us just how diverse herbivorous dinosaurs had become in the Late Cretaceous.

Its discovery highlights an ecosystem where hadrosaurids had adapted in ways that suited South America’s southern reaches. At a time when Earth’s continents and climates were shifting, this creature likely thrived in river valleys and floodplains, using its specialized mouth to browse efficiently. The more we uncover about this ornithopod, the clearer the picture becomes of what life was like just before the curtain fell on the Mesozoic Era.

Huallasaurus Key Facts

| Keyword | Fact |

|---|---|

| Pronunciation | WAH-yah-SORE-us |

| Meaning of name | Duck Lizard |

| Group | Ornithopoda (Hadrosauridae) |

| Type Species | Huallasaurus australis |

| Diet | Herbivore |

| When it Lived | 83.5 to 66.0 MYA |

| Period | Late Cretaceous |

| Epoch | Upper Campanian to Lower Maastrichtian |

| Length | ~23-30 feet |

| Height | ~10 feet |

| Weight | ~2-3 tons |

| Mobility | Moved (mostly) on four legs |

| First Discovery | 1980s, discoverer not well-documented |

| Described by | 1984 by José Fernando Bonaparte, María del Rosario Franchi, Jaime Eduardo Powell, and E. G. Sepúlveda |

| Holotype | MACN-PV 2 |

| Location of first find | Los Alamitos Formation, Rio Negro, Argentina |

Huallasaurus Origins, Taxonomy and Timeline

The name Huallasaurus is both descriptive and regionally rooted. It blends “hualla,” a word from the Mapudungun language meaning “duck,” with the Greek sauros, meaning “lizard.” While simple, the name reflects a feature shared with many of its relatives: a broad, flat beak not unlike that of modern waterfowl. Yet, despite the nickname “duck-billed,” these dinosaurs had complex skulls and jaws capable of highly efficient chewing—an innovation in the dinosaur world.

Taxonomically, this dinosaur belongs to Ornithopoda, a diverse group of ornithischian herbivores, and more specifically to the Hadrosauridae family. Within this group, Huallasaurus is classified as a member of the subfamily Saurolophinae, a clade of hadrosaurs characterized by their generally solid crests or lack thereof. Huallasaurus is currently represented by a single species, Huallasaurus australis. The species name “australis” means “southern,” a nod to the Patagonian region where its remains were found. There are no known subspecies, and its classification within saurolophine hadrosaurids adds another piece to the complex puzzle of South American dinosaur diversity in the Late Cretaceous.

This dinosaur lived between roughly 75 and 66 million years ago, during the Late Campanian to Maastrichtian stages of the Late Cretaceous. These were the final chapters of the Mesozoic Era, marked by shifting climates and dynamic ecosystems. Gondwana had largely fragmented by this time and South America existed as a relatively isolated continent. In Patagonia, life thrived in diverse environments—from forested floodplains to open woodlands—creating a rich setting where herbivores like Huallasaurus could flourish right up until the end of the dinosaur era.

Discovery & Fossil Evidence

Huallasaurus is based on numerous specimens collected in the 1980s from the Los Alamitos Formation—an important Late Cretaceous deposit in Argentina’s Río Negro Province. These fossils were originally described in 1984 as a new species of Kritosaurus, named Kritosaurus australis. However, continued study and comparisons with other hadrosaurids revealed distinct anatomical features that warranted separation from Kritosaurus. As a result, the species was reclassified in 2022 as a new genus, Huallasaurus, with the specimen MACN-PV 2 designated as the holotype.

The known material attributed to Huallasaurus includes fragmentary remains from both the cranial and postcranial skeleton. These include portions of the skull, such as elements of the maxilla and braincase, along with vertebrae, limb bones, pelvic elements, and parts of the shoulder girdle. While incomplete, these fossils preserve enough anatomical detail to distinguish Huallasaurus from other South American hadrosaurids and to clarify its placement within the subfamily Saurolophinae.

Despite their fragmentary nature, these remains offer valuable insight into the diversity and evolutionary history of hadrosaurid dinosaurs in South America during the final stages of the Cretaceous. They highlight the persistence and regional differentiation of duck-billed dinosaurs in Gondwana, contributing to a broader understanding of how these animals adapted and radiated in southern ecosystems near the end of the Mesozoic.

Huallasaurus Size and Description

Like most other saurolophines, Huallasaurus was likely a primarily quadrupedal herbivore, walking on all four limbs as it foraged across the landscape. However, it may have occasionally reared up onto its hind legs to access higher vegetation, using its strong hindlimbs and tail for balance. Its build combined stability and mobility, allowing it to move efficiently through its environment while remaining alert to potential predators.

Short description of Huallasaurus

The overall shape of this dinosaur reflects the classic hadrosaurid blueprint. Its head was elongated with a flat, duck-like beak ideal for cropping vegetation. The neck was moderately long, supporting the head without excess strain. Along the spine, it had strong vertebrae that supported its tail and helped with balance.

The limbs of this dinosaur were well-developed and built for steady movement. Its powerful hind legs likely provided most of the propulsion, while the shorter forelimbs—though not as long—were also adapted for weight-bearing, especially during travel. This quadrupedal ability is inferred from close relatives within the hadrosaur group, many of which show similar adaptations. A long, muscular tail helped counterbalance the front of the body, providing stability while on the move. Although no skin impressions are known from Huallasaurus, comparisons with related species suggest it likely had a rough, scaly texture that may have varied across different parts of its body.

Size and Weight of Type Species

Estimating the exact size of Huallasaurus is challenging due to the fragmentary nature of its remains, but based on comparisons with related saurolophine hadrosaurs, it likely reached lengths of around 7 to 9 meters (23 to 30 feet). Unlike some hadrosaurids from North America that grew to immense sizes, this places it among the mid-sized hadrosaurs—large enough to deter many predators, yet still agile enough to navigate the varied terrain of Late Cretaceous Patagonia.

Given the terrain it lived in—ranging from floodplains to forested valleys—its size would have allowed it to travel efficiently and access a wide variety of plant matter. It likely used its “beak” to crop vegetation and its tightly packed dental batteries to grind it down, making it one of the more advanced herbivores of its ecosystem.

The Dinosaur in Detail

Hadrosaurs are best known for their unique skull structures and specialized adaptations for plant-eating. Although the skull of Huallasaurus is only partially known, its saurolophine relatives often featured modest or solid cranial ornamentation rather than the elaborate hollow crests seen in lambeosaurines. These features may still have served for species recognition or social signaling, though likely in a less acoustically complex way than in their crested cousins.

The teeth of hadrosaurids represent some of the most advanced dental adaptations in the dinosaur world. In Huallasaurus, as in other hadrosaurids, the jaws likely housed tightly packed dental batteries—vertical stacks of teeth that formed extensive grinding surfaces. These structures allowed the animal to process a wide range of fibrous vegetation, including plants that earlier herbivores would have struggled to digest. Its jaws were capable of complex movements involving both vertical and sideways motion, producing a form of chewing rare among reptiles and functionally convergent with that of mammals.

The skeletal build of hadrosaurids—including Huallasaurus—reflects an animal built for steady movement across its environment in search of abundant plant resources. It likely traveled in herds, possibly migrating with the seasons in search of fresh vegetation. Herd behavior, if confirmed, would align with evidence from trackways and mass fossil assemblages of similar dinosaurs found in other parts of the world. Altogether, this creature represents a fine-tuned herbivore, well-adapted to its time and place.

Interesting Points about Huallasaurus

- The name combines an Indigenous Mapudungun word with Greek, a unique cross-cultural naming convention.

- It lived during the very end of the Cretaceous, just before the extinction event.

- Its complex teeth allowed it to process tougher vegetation than other dinosaurian herbivores.

- The fossil was found in Patagonia, a region rich with Late Cretaceous dinosaur diversity.

- It belonged to a group capable of both bipedal and quadrupedal movement, depending on behavior or need.

Contemporary Dinosaurs

Sharing the same Late Cretaceous landscapes as Huallasaurus was Aucasaurus, a stocky abelisaurid theropod with a deep, short skull and reduced forelimbs. Though not among the largest predators of its time, Aucasaurus was likely a formidable threat to smaller or juvenile hadrosaurids. Its presence may have influenced the behavior of herbivore herds, encouraging vigilance and possibly promoting group defense strategies.

Towering above most other dinosaurs in the region was Aeolosaurus, a titanosaurian sauropod known for its elongated neck and massive body. Unlike the low-browsing Huallasaurus, Aeolosaurus would have fed from the tree canopy, occupying a different feeding niche. Despite their size disparity, these two herbivores likely shared space, each utilizing different layers of the environment to minimize competition.

Another dinosaur that shared the landscape with our main herbivore is Secernosaurus, another hadrosaurid from South America. Its presence suggests that multiple duck-billed species lived in proximity, possibly using subtle differences in diet or habitat preference to avoid direct competition. These animals might have foraged in overlapping territories but focused on different plants or feeding heights.

Another contemporary is Talenkauen, a small and agile ornithopod. Unlike the robust Huallasaurus, Talenkauen likely relied on speed and maneuverability to escape predators. It may have lived on the edges of forested areas, darting between cover and feeding on soft-leaved plants. Though not directly related, its coexistence illustrates the range of body plans and survival strategies among herbivores in Late Cretaceous Patagonia.

Huallasaurus in its Natural Habitat

The world of Huallasaurus was vibrant and dynamic. During the Late Cretaceous, Patagonia featured broad floodplains, braided rivers, and seasonal wetlands shaped by shifting water levels and sedimentation. The landscape was lush with plant life—ferns, cycads, and conifers mingled with the rising diversity of flowering plants, forming a mosaic of feeding opportunities for large herbivores.

As a hadrosaurid, Huallasaurus likely used its broad beak to crop leaves and low-growing plants, then chewed the material with rows of grinding teeth specialized for breaking down tough vegetation. It probably moved on all fours while travelling, though it could rear up on its hind legs situationally, such as when feeding. With eyes placed to the sides of its head, it would have had a wide field of view—useful for spotting predators such as Aucasaurus.

This dinosaur played an active role in its ecosystem. As it foraged and moved through the landscape, it may have helped disperse seeds and opened up vegetation, influencing plant community structure—much like large modern herbivores do today. Herding behavior inferred from related species suggests that it may have migrated seasonally, with group living offering protection and social interaction during nesting or foraging cycles. Though its exact lifespan is uncertain, comparable species show evidence of lives that could span several decades.

Frequently Asked Questions

Size estimates for Huallasaurus are rough due to the fragmentary nature of its remains. However, based on comparisons with related hadrosaurids, it likely measured between 25 and 33 feet (7.5–10 meters) in length, stood around 10 to 12 feet (3–3.7 meters) tall at the hips, and may have weighed between 2 and 3.5 tons.

It lived during the Late Cretaceous, sometime around about 83.5 to 66 million years ago.

This dinosaur was an herbivore, feeding on plants using a flat beak and complex grinding teeth.

Its fossils were found in the Los Alamitos Formation in Patagonia, Argentina, during the 1980s.

It moved mostly on four legs but may have shifted to two legs on occasion while feeding.

While not confirmed, it probably lived in herds like many other hadrosaurids, providing safety in numbers.

Sources

The information in this article is based on various sources, drawing on scientific research, fossil evidence, and expert analysis. The aim is to provide a comprehensive and accurate overview of Huallasaurus. However, please be aware that our understanding of dinosaurs and their world is constantly evolving as new discoveries are made.

- https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/02724631003763508

- https://www.researchgate.net/publication/358834727_A_new_hadrosaurid_Dinosauria_Ornithischia_from_the_Late_Cretaceous_of_northern_Patagonia_and_the_radiation_of_South_American_hadrosaurids

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC10275600/

This article was last fact checked: Joey Arboleda, 05-01-2025

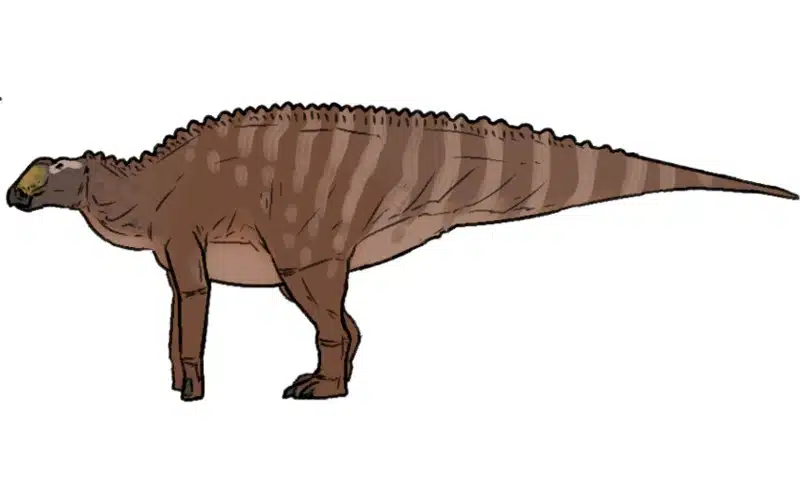

Featured Image Credit: Connor Ashbridge, CC BY-SA 4.0, via Wikimedia Commons